The hope that deep waters below the divers’ range still held healthy populations that could act as a genetic reservoir was dashed when the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (WDFW) annual deepwater sampling trawls came up with similar results: the “near extirpation” of sunflower sea stars throughout the state’s inland waters.

The inescapable fact is that what was once the most commonly seen invertebrate in the Salish Sea has almost disappeared in just a few years.

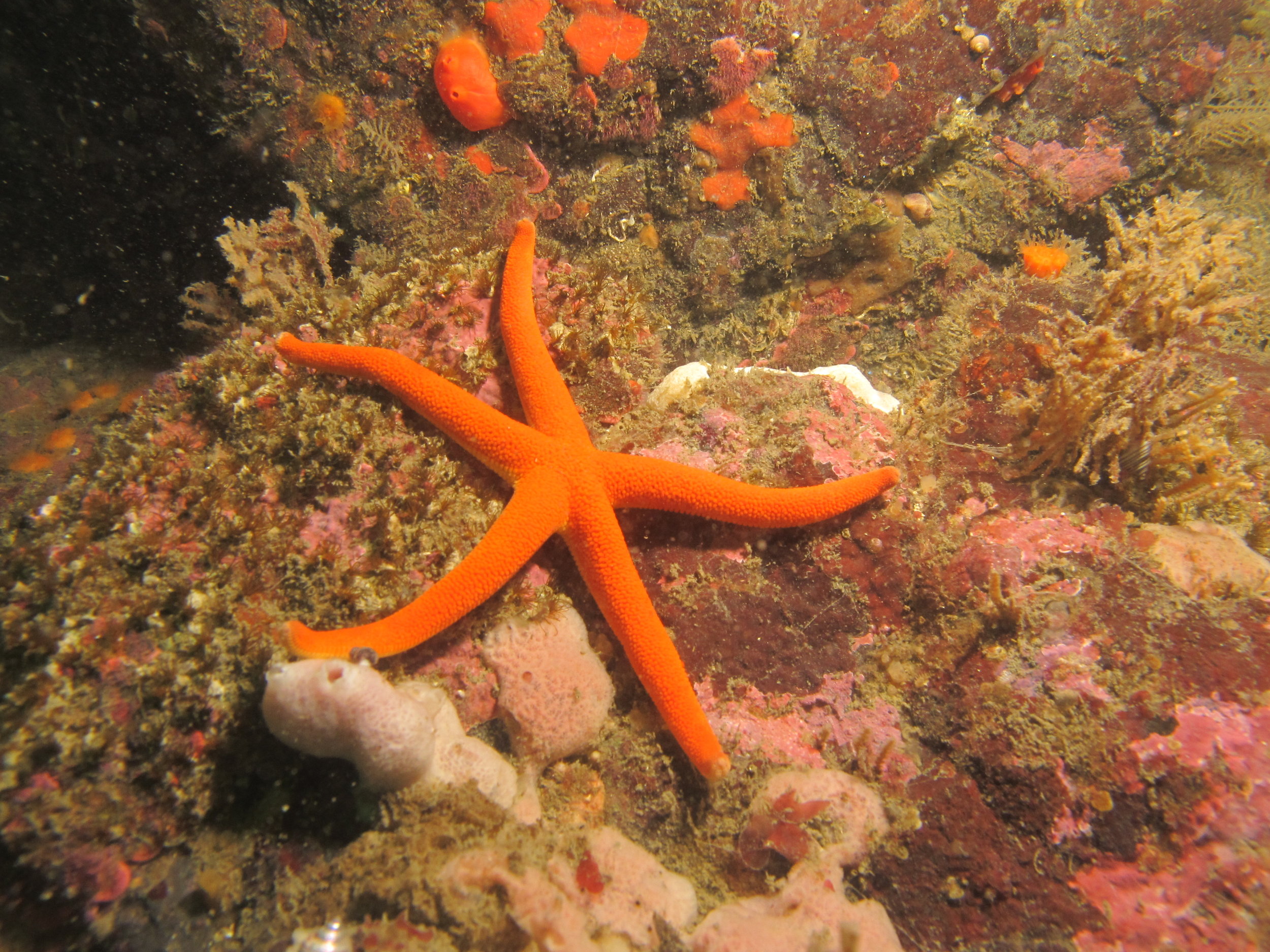

Sunflowers are the magnificent beasts of the sea star world, with as many as 24 arms that from tip to tip can measure up to the size of a nine-year-old child. And they use those arms to chase down sea urchins as enthusiastically as a nine-year-old chasing down an ice cream truck on a hot summer day. Sunflower predation is such an important control on urchin populations (which left unchecked can raze kelp forests) that the sea stars are considered ecosystem engineers. Remove them from the picture and we’re likely facing a domino effect of negative outcomes for all kinds of plant and animal species. Evidence of such a “trophic cascade” is already being found by researchers in British Columbia.

SeaDoc and our partners at REEF, WDFW, Cornell University, Vancouver Aquarium, and the Seattle Aquarium, which brought together experts for an emergency scientific summit on SSWD a year ago, have been at ground zero of this epidemic from the start. And with such startlingly clear results from the science and such alarming potential for further damage to the ecosystem, we feel there’s no time to lose in moving forward quickly with sunflower sea star conservation.