Salish Sea Species Facts

designed and written by Anneke Ivans

Southern Resident Killer Whales

Here in the Salish Sea, there are three distinct subtypes (or ecotypes) of killer whales. The most well-known are the Southern Resident killer whales (Orcinus Orca). The other ecotypes are Transient and Offshore killer whales. Southern Residents live in close-knit, matriarchal social communities led by adult female members. We can differentiate Southern Resident killer whales from other ecotypes based on their individual markings, behavior, genetics, and their preferred prey. In 2005, Southern Resident orcas were listed as endangered on the Endangered Species Act. The three main factors that have caused their decline are their dwindling preferred prey, Chinook salmon, disturbance by vessels, and increasing levels of contaminants in their blubber.

DID YOU KNOW?

There are three distinct pods of Southern Resident killer whales known as J, K, and L pods. In just 5 years from 1996 to 2001, their population decreased by 20% and they are currently endangered in both the U.S. and Canada.

These marine mammals communicate acoustically with one another to hunt and navigate the ocean. Sharing the ocean with vessels such as ferries, commercial fishers, and whale watching boats, there has been an increase in noise level that carries underwater. Such noise can interfere with orcas’ ability to communicate with one another, causing them to speak louder in the presence of boats on the water.

Southern Resident killer whales live in close proximity to humans and have been shown to have antimicrobial resistant bacteria in their respiratory tracts.

Southern Resident killer whales communicate in calls that are specific to their pod. There are three distinct classifications of communication: clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls.

As the seasons change, so do the feeding habits of the Southern Resident killer whales. Chinook salmon make up half of their diet in the fall and nearly 100% in spring.

While Southern Residents spend some of their life in the Salish Sea, they range from the outer coast of Vancouver Island to California.

Lack of available Chinook salmon causes significant stress on their reproduction, specifically during the late stages of pregnancy, with 69% of recorded pregnancies between 2008 to 2014 being unsuccessful.

Photo by Katy Foster. Banner photo by Gale Swigart.

Keep up with Southern Residents Killer Whale news! (No Spam)

FURTHER READING

Offshore Killer Whale Facts

Offshore killer whales (Orcinus orca) are genetically distinct from both Southern Resident and Transient ecotypes, being more closely related to Residents than Transients. While there is limited knowledge of this ecotype, we have found that Offshore killer whales feed primarily on sharks and fish and can be found in the open ocean stretching from the eastern Aleutian Islands of Alaska to southern California.

Worn teeth of an offshore killer whale

DID YOU KNOW?

In the late 1980s, these killer whales were observed mainly offshore and were given the name “offshores.”

Field observations first documented sharks as prey of Offshore killer whales in 2011. Due to the tough nature of the shark’s skin, the teeth of Offshore killer whales have shown significantly more wear than that of Resident and Transient killer whales.

A serious cause of disease in Offshore killer whales can be traced to the mouth. Dental disease, specifically, periodontal and endodontic diseases, are common for this species. In the case of deceased whale strandings, the teeth are a vital component for assessing health when other tissue may no longer be a viable clue.

The population of offshore killer whales that ranges widely in continental shelf waters from southern California to the eastern Aleutian Islands is considered relatively stable and numbers about 300 individuals.

Get our free monthly newsletter!

Transient Killer Whale Facts

Transient killer whales (Orcinus orca), also known as Bigg’s killer whales, are unlike the Southern Residents, exclusively eating marine mammals, including harbor seals, harbor porpoises, and Steller sea lions. They can be found from southern Alaska to central California, but despite their name implying frequent movement, they often call the Salish Sea home.

DID YOU KNOW?

The vocal behavior of Transient killer whales is significantly different from that of Southern Resident killer whales. While fish-eating Southern Residents call to one another during foraging, Transient killer whales remain silent in order to successfully surprise and catch their marine mammal prey. Once they catch their prey, they vocalize more readily with one another.

Transient killer whales use a wide range of habitats and some pods spend a significant amount of time in shallow waters less than 5 meters deep, hunting for food in intertidal waters during high tide. One group of transients in the Salish Sea called the T065A matrilineal group, have been recorded intentionally stranding to scare seals they are hunting into the water.

Transient and Southern Resident killer whales avoid one another. The two different ecotypes do not interact, do not interbreed and are genetically distinct. From 2011 to 2017, there was a steady increase in the number of Transient killer whales coming to the Salish Sea. At the same time, likely due to salmon declines, there was a decrease in the number of Southern Residents in the region.

Breaching transient killer whale by Ken Rea. Banner photo by Arial Brewer.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Dall’s Porpoise Facts

Dall’s porpoises (Phocoenoides dalli) are not shy mammals. In fact, they are often found bow-riding on the wake of moving vessels. They have a widespread distribution in the north Pacific Ocean, traveling between bays, nearshore waters, and the open ocean. Like the harbor porpoise, the Dall’s porpoise can be found in the Salish Sea year-round, but there is evidence that the two species use separate resources and habitats at different times.

DID YOU KNOW?

Adult males grow to be about 6.6 feet long, while adult females grow to around 6.3 feet long.

In some places, like the Bering Sea they hunt mainly at night in shallow water, feeding on forage fish and squid.

The main predator of Dall’s porpoises is Transient killer whales.

Despite being two separate species that do not form mixed pods, Dall’s porpoise and harbor porpoises will occasionally mate. Hybridization has been recorded as generally occurring between male harbor porpoises and female Dall’s porpoises.

Dall’s porpoises echolocate and produce narrow-band, high-frequency clicks and pulses to communicate with one another and find food. Narrow-band high-frequency pulses are known as a very specialized form of acoustic communication that killer whales and other toothed-whale predators are unable to detect.

Photo by Greg Schechter (Creative Commons Flickr). Banner photo by Jim Pfeiffenberger (Creative Commons Flickr).

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Harbor Porpoise Facts

The harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) is a shy species of porpoise that inhabits the Salish Sea year-round. They are the smallest species of cetacean (a group that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises) in the Salish Sea. They reach an average length of 5 to 5 ½ feet and weighing up to 170 pounds. Harbor porpoises generally live in groups of 2 to 3 and are widely distributed throughout the Salish Sea. While they are one of the most abundant and frequently sighted cetacean in the Salish Sea, we know very little about their ecology, such as their population, life cycle, genetics, and behavior.

DID YOU KNOW?

Harbor porpoises are acoustic animals that produce underwater clicks to help them navigate and find their prey which includes fish and cephalopods. Studies have shown that they echolocate most during the night.

Although they regularly surface for a breath of air, harbor porpoises may be difficult to spot because of their short, triangular dorsal fin that hardly raises out of the water when they surface. In the Salish Sea, harbor porpoises only spend about 23% of their time at the surface. The maximum recorded dive for a harbor porpoise was 740 feet!

Immature harbor porpoises cannot dive as deep as adults, therefore limiting the underwater habitat that calves live in. Increased boat traffic on the surface may be affecting porpoise calves much differently than adults.

Harbor porpoises are the most commonly stranded cetacean in the Salish Sea. This may be due to a growing population of harbor porpoises and increased surveillance by marine mammal stranding networks.

Photos by Florian Graner.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

North American River Otter Facts

The North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) is a widespread species with thriving populations across the United States. They can be found from inland rivers to the coastline, relying on freshwater and marine ecosystems to catch prey. Marine-foraging river otters eat gunnel, sculpin, pricklebacks, rockfish, flounder, cod, herring, kelp crabs, marine worms, and even gull chicks. Alternating between land and water, they are frequently seen in the Salish Sea meandering in and around the seashore, frequently leaving scat on docks.

DID YOU KNOW?

Marine-foraging river otters are unique in that they split their time between the ocean and land, therefore playing a vital role in the marine-terrestrial ecosystem by fertilizing the land and vegetation in close proximity to the ocean.

River otters use latrine sites along the coastline to scent-mark specific locations and communicate with each other. Scents can communicate important information such as territory lines, health, and reproductive status.

When you see a big group of river otters, you’re likely not seeing a family. It’s probably a group of foraging adult males working together to herd fish and other prey into a tight bundle for hunting.

River otters can dive 60 feet below the surface of water looking for prey.

47% of river otter deaths in the Salish Sea are caused by humans. This includes death caused by vehicle strikes and gunshots.

River otters tend to avoid interacting with humans but there have been recorded attacks on people. It’s important to give river otters their space and not harass them.

Historically, river otters were present at every watershed throughout the continental United States. However, after years of the unregulated harvest of their fur pelts in concert with the destruction of their habitat in the early 1900s, river otters were completely eradicated from 11 of these 48 states. After conservation efforts were made by state, federal, and tribal agencies, the population has steadily increased over the last 50 years.

Photo by Steven & Sylvia Oboler. Banner photo by Kendrick Moholt.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Steller Sea Lion Facts

Photo by Alison Engle. Banner photo by Alexander Patia.

Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) can be found along the North American coast, ranging from southeastern Alaska to central California, and all the way to eastern Russia. They hunt for prey in the water and frequently haul-out to rest on islands with rocky shorelines, beaches, and docks. During the summer months, they congregate at rookeries or breeding grounds where they breed, give birth, and nurse their pups. In Alaska, it was found that females return to the rookery where they were born in order to breed.

DID YOU KNOW?

Their preferred prey in Washington state is fish such as Pacific hake, rockfish, skates, flounders, herring, salmon, smelt, shad, and cod.

Steller sea lions are the world’s largest species of sea lions. The adult male Steller sea lion can weigh up to 2,400 pounds and will grow to be 3 times the size of an adult male grizzly bear.

Steller sea lions communicate with one another by hissing and belching. The bulls, or adult males, are usually responsible for the loud noises, which are meant to ward off other males during mating season. They also communicate underwater, using clicks, barks, and low-frequency pulses.

The main predators of Steller sea lions are Transient, or Bigg’s killer whales, Pacific sleeper sharks, and historically, humans.

In 1979, the Steller sea lion population was at an estimated number of 18,313 animals. In 1990, they were federally listed as a threatened species. This listing, in addition to the protection afforded by the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, has increased their population to more than 70,000 animals.

The eastern distinct population segment, which includes Steller sea lions originating from rookeries east of Cape Suckling in Alaska, has since recovered and as of 2013 was no longer listed federally and in 2015 no longer listed in Washington State—a significant achievement under the Endangered Species Act. The western distinct population segment (DPS) remains endangered.

Photo by Jennifer Vanderhoof.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Rockfish Facts

Rockfish (Sebastes spp.) are a diverse group of fish that live in nearshore waters where their preferred habitat is in disheveled piles of loose rocks or along the rocky seafloor near the intertidal zone. There are more than 100 species of rockfish around the world and 70 of these species can be found in the Northeast Pacific ocean and at least 28 species here in the Salish Sea. a natural defense against predators, rockfish have venom lining the spiny tissue in the grooves of their dorsal, anal, and pelvic spines.

DID YOU KNOW?

Predators of rockfish are marine birds, marine mammals, and even other fish such as Chinook salmon.

Several rockfish species (Yelloweye and Quillback) are some of the longest-lived species in the Salish Sea

Some species of rockfish choose to spend their entire lives at the same site, finding their home among the rocks. Other species such as the black rockfish (Sebastes melanops) live in schools and follow the food.

Adult rockfish are typically demersal, meaning they live near the bottom of the seafloor, or stay in the midwater between the surface and seafloor. Bottom dwellers find a home among the reef and are usually brightly colored, whereas midwater rockfish live in schools above the reefs and are usually brown, black, or grey.

In the Salish Sea, rockfish populations were heavily overfished in the 1970s and 1980s. Populations of many species of rockfish are still very low today, warranting some species to be listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Photo by David Hicks. Banner photo by Nirupan Nigam.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Chinook Salmon Facts

Photo by mypubliclands (Creative Commons Flickr).

Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) play a vital role in the Pacific Northwest’s ecological food web. Juvenile Chinook salmon feed primarily on terrestrial and aquatic insects, crustaceans, crab larvae, and amphipods, while mature Chinook salmon feed on forage fish such as smelt, Pacific sand lance, Pacific herring, and pricklebacks. Chinook salmon are important prey for seabirds, grizzly bears, harbor seals, Steller sea lions, and Southern Resident killer whales. Chinook are found throughout the Northern Pacific Ocean, but currently, many of the wild populations of these salmon are endangered. Their decline has been caused by habitat loss, development, migration barriers, overfishing, overuse of water resources, loss of genetic diversity, salmon farms, and climate change.

DID YOU KNOW?

The endangered Southern Resident killer whales rely on Chinook salmon as their main source of prey. From 1975 to 2015, the amount of Chinook salmon consumed by killer whales and pinnipeds increased drastically from 6,100 to 15,200 tons, which is equivalent to an increase of 5 to 31.5 million individual salmon.

For more than 100 years, hatchery programs have been used to augment wild salmon populations. Hatchery managers are trying to improve this tool while minimizing impact on wild Chinook.

Chinook salmon possess a natural genetic color polymorphism, which gives their tissue and eggs a red or white coloration.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Tufted Puffin Facts

The tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) is a seabird known for its white-yellow tufts and distinguished, bright orange bill. Built for catching fish, they have waterproof feathers and small wings that act as fins to propel them through the water to great depths in search of fish. The tufted puffin spends almost the entire year at sea, only coming to shore to lay eggs and raise their young. They breed on isolated islands in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Strait of Georgia where the land is soft enough to tunnel burrows for nesting.

DID YOU KNOW?

Tufted puffins were once common in the Salish Sea with more than 40 puffin nesting colonies in Washington State. However, SeaDoc research from 2015 found that the population of puffins has decreased by 90% to less than 3,000 birds.

Adult tufted puffins only spend a few months on land during the summer. During this time, they breed and care for their young. The rest of their lives are spent on the open ocean searching for food.

Tufted puffins are skilled divers, but need to use their webbed feet to run across the water, building up momentum before going airborne.

Their iconic orange beaks are equipped with spikes inside which allows them to open their mouths underwater and collect fish as they hunt, carrying up to 20 fish at a time.

They are able to cool themselves down and regulate their body temperature after exerting energy during flight by using their beaks as heat regulators.

Photo by Bill Braire. Banner photo by Eric Ellingson (Creative Commons Flickr)

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Marbled Murrelet Facts

The marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a small unique bird that gets its name from its changing feather patterns. In the winter, they turn a stark white and black color, and during their summer breeding season, they become light brown and white, taking on a marbled effect. The marbled murrelet belongs to the Alcidae family along with the tufted puffin and pigeon guillemot. This small seabird is about the size of a robin and has short, powerful wings covered in a dense layer of waterproof feathers to help them dive underwater for fish.

DID YOU KNOW?

Their habitat differs from other alcids, splitting their time between the ocean and land, taking up residence in the forests of old-growth trees to nest.

Because marbled murrelets have evolved to swim through water, their webbed, clunky feet are not ideal for building nests and maneuvering across branches. Their nests will often consist of a simple patch of soft moss or lichen on wide branches, making old-growth trees the optimal nesting place.

They can dive up to almost 45 feet underwater. Using their small wings to propel them efficiently through the water and their webbed feet to steer.

For such a small bird, they lay uncommonly large eggs, about the size of a chicken egg.

Crows and Jays, members of the Corvid Family, are the most significant predator of marbled murrelets eggs throughout Washington, Oregon, and California.

Marbled murrelets have been referred to as the "enigma of the Pacific" because of their elusive behavior and hard-to-find nests.

The marbled murrelet has been listed as a threatened species under the US Federal Endangered Species Act in Washington, Oregon, and California. The recovery of their population relies on restoring and preserving their breeding habitat.

Photo by Eric Ellingson. Banner photo by David Ayers.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

FURTHER READING

Black Oystercatcher Facts

The black oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) is a frequently sighted bird that calls the Salish Sea home year-round. It is easily recognizable by its black feathers and long, red bill. You might see a black oystercatcher poking around the tide pools during mid and high tide, on the hunt for food. Its pointed, narrow bill is useful when searching for food along the rocky shoreline. The population of black oystercatchers is a valuable indicator of the health of intertidal ecosystems as their presence means there is an abundance of marine life flourishing within the rocky terrain.

DID YOU KNOW?

The black oystercatcher does not actually eat oysters. Instead, it feeds on marine snails such as limpets and periwinkles, mussels, marine worms, and pinto abalone.

The rocky seashore is the black oystercatcher’s home. In addition to searching for small marine prey in the tidepools, it also tends to build its nests just above the high tide line on the shores of isolated islands.

The sex of a black oystercatcher can be determined by looking at the pattern of the iris in their eyes. If an oystercatcher has several flecks throughout its entire iris, it is a female, and if the iris has minimal or no eye flecks, it is a male.

The global population of black oystercatchers numbers around 10,000 individuals. About 80% of their population can be found living along the coastline between Alaska and British Columbia.

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil spill into Alaska’s Prince William Sound had several negative impacts on the black oystercatcher population. The spill contaminated their marine habitat and caused a major reduction in mussel populations. This sharp decline in their primary prey decreased their breeding and foraging behavior. However, in just two years, their population had recovered significantly from the oil contamination.

Photo by Alexander Pati. Banner photo by Diana Robinson (Creative Commons Flickr).

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Bald Eagle Facts

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is an iconic species and has been the United States’ national bird since 1782. This majestic raptor can be found throughout the United States and Canada and in parts of northern Mexico. In Washington State, the wintering bald eagle population, which includes resident breeders and seasonal migrants, is growing and has been estimated to eventually reach a steady state at 6,000 birds.

Western Washington has the largest population of bald eagles in the Pacific Northwest. These opportunistic raptors hunt and scavenge, often feeding on salmon and other fish, and even sea birds (Middleton et al., 2018; Henson et al., 2019). Their excellent eyesight and aerodynamic body allows them to spot, and drop-in on prey from 1,000 feet in the air. In the early twentieth century, bald eagles were once regarded as vermin and a threat to livestock.

During this time their populations dramatically declined due to hunting, poisoning, and the shell-thinning effects of now-illegal insecticides like DDT (Stinson et al., 2007). When DDT was banned in the U.S. in 1972 and protections were set in place to reduce persecution and protect habitat, eagle populations rebounded.The recovery of bald eagles is now considered a great conservation success story.

DID YOU KNOW

A bald eagle has an average wingspan of 6 feet (2m)! These massive wings have finger-like gaps in their feathers to allow for excellent precision maneuvering through the air.

An eagle’s talons are among the strongest in the bird world. They use these long, sharp talons to hunt and catch fish as they swoop across the water, often holding multiple forage fish at a time.

Bald eagles are thought to live over 20 years. Scientists followed one banded eagle that lived to at least 28 years.

Bald eagles aren’t born with their distinctive white head. Their plumage (feather patterns) change throughout their youth. Each year from spring to fall, the eagle molts (sheds) all of its feathers, replacing old feathers with new ones. The feather patterns gradually change with age. Bald eagles acquire their distinctive adult plumage and white head by 5 years of age.

In the Salish Sea, bald eagles are known predators of sea birds. Even the sea birds know it! Sea birds alter their behavior in the presence of bald eagles.

Bald eagle populations have been increasing and the species is currently listed by the International Union of Concerned Scientists (IUCN) as “Least Concern,” however, habitat loss and degradation of suitable nesting sites from urbanization is still a threat to their survival.

FURTHER READING/Viewing

FURTHER READING

learn more about the salish sea!

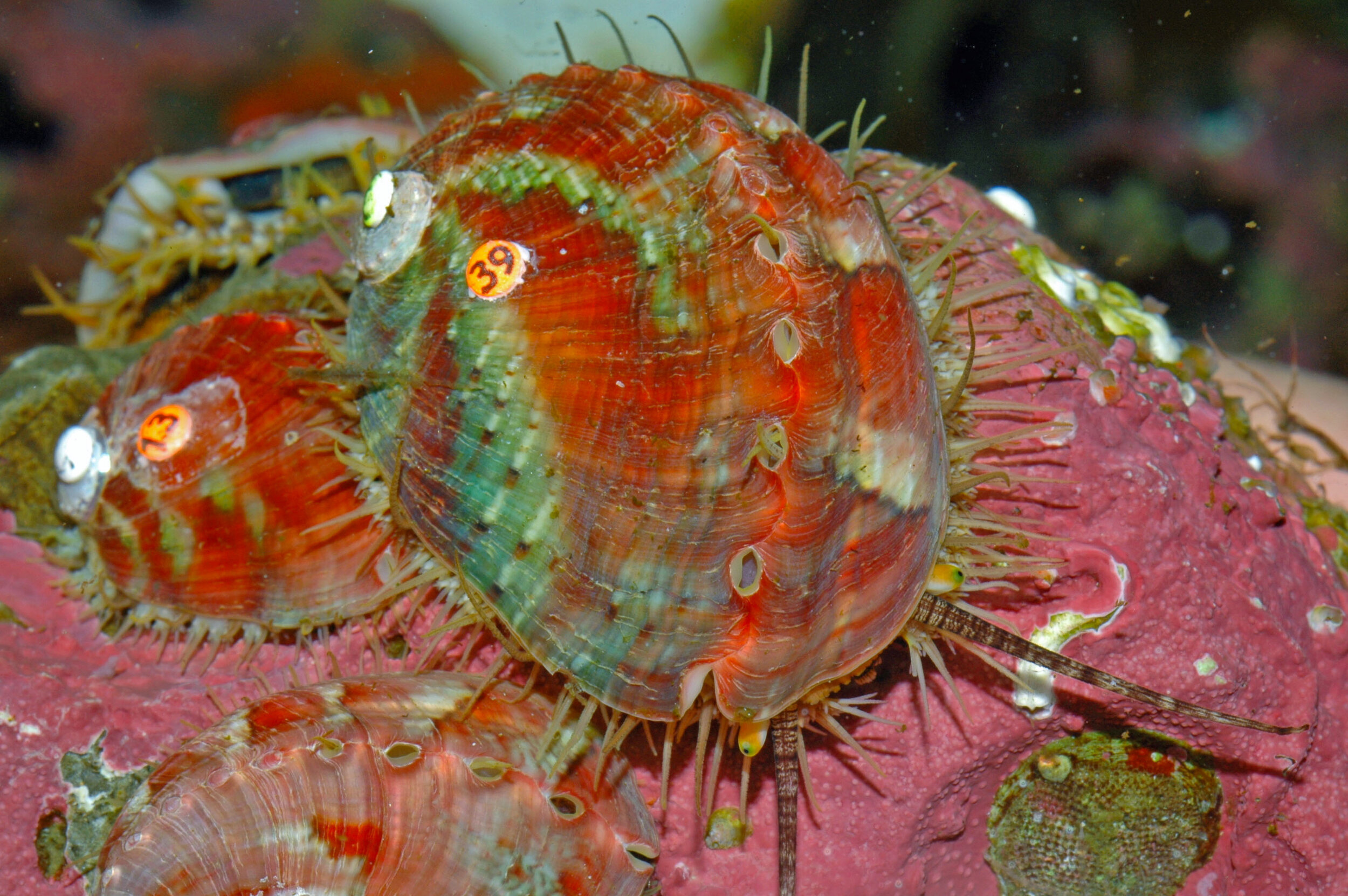

Pinto Abalone Facts

Pinto abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana) are sea snails with colorful shells that can be found along the rocky seashore. Unfortunately, their population has declined by 97% in Washington State due to the over-harvesting. Low remaining numbers have hindered their ability to reproduce in the wild because they are “broadcast spawners,” meaning when a male releases sperm, a female needs to be nearby for her eggs to be fertilized. However, because of their small population, they have difficulty reproducing in the wild. In 2019, pinto abalone were listed as endangered in Washington State and can no longer be harvested in the state.

DID YOU KNOW?

Pinto abalone thrive in areas with heavy kelp and rocky surfaces where crustose coralline algae grows. This has the best potential to support abalone life as they can feed on the abundant algae.

The brightly colored pinto abalone has noticeable rings running across the length of the shell. Each year another ring is formed around the spire of the shell during the middle of summer. This way, you can tell how old an abalone is by counting the number of rings on its shell.

A natural predator of the pinto abalone is the sea otter, cracking open the shell in search of the meat inside.

The underside of the shell is made up of a nacreous material, known to us as mother of pearl. This is another common reason they have been so heavily foraged throughout the years.

Photo by Janna Nichols. Banner photo by Josh Bouma.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Sunflower Sea Star Facts

Sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) are marine invertebrates also called starfish by some and asteroids by scientists, that belong to the same family as as sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and sand dollars. Sunflower sea stars play a critical role in our marine ecosystem because they are natural predators of sea urchins, which are notorious for destroying kelp forests. However, sunflower sea star populations have declined to critically low levels from a disease called Sea Star Wasting Syndrome. This disease has killed 99.2% of the overall population of Pycnopodia spp. in Washington state.

DID YOU KNOW?

Sunflower sea stars are carnivores that feed on both living and dead prey with a diet consisting of opalescent squid, clams, spiny dogfish, herring, sea urchins, mollusks, and even other sea stars.

The adult sunflower sea star can have up to 24 limbs, each covered in extremely powerful, tiny suction cups that allow them to move along the sand climbing over rocks and other marine terrain.

Sunflower sea stars are important for maintaining a healthy marine ecosystem. In some places, the decline of sunflower sea stars caused by Sea Star Wasting Syndrome has resulted in a 311% increase in medium-sized sea urchins, which has decreased kelp forest densities by 30%.

When working to hunt or find dead food, they perceive light, chemical, and mechanical changes in their environment using the outer ends of each arm that function as sensors.

In 2020, they were placed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s critically endangered species list due to Sea Star Wasting Syndrome. This listing, which affords sunflower sea stars legal protection measures, happened with the help and collaboration of more than 60 different organizations, including SeaDoc Society.

Photos by Janna Nichols.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

FURTHER READING

Falling Stars: Once Abundant Sea Stars Imperiled by Disease Along the West Coast

Devastating Transboundary Impacts of Sea Star Wasting Disease on Subtidal Asteroids

Disease epidemic and a marine heat wave are associated with the continental-scale collapse of a pivotal predator (Pycnopodia helianthoides)

Giant Pacific Octopus Facts

Photo by Jacqueline Winter. Banner photo by Bruce Kerwin.

The giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is the largest octopus species in the world and can be found right here in the Salish Sea. It prefers shallow and nearshore marine environments, seeking out covered, secluded dens to hide from predators beneath the protection of rocky structures. The giant Pacific octopus inhabits the entire Pacific Rim from the western coastline of North America all the way to Korea. It has a longer lifespan than most other octopods, living between 3 to 5 years.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most giant Pacific octopuses weigh less than 70 pounds and can stretch 15 feet in length. The largest confirmed giant Pacific octopus found weighed 437 pounds (198.2 kilograms).

At the end of her life, the female octopus will lay between 120,000 and 400,000 eggs and stop eating for around 6 months until the eggs have hatched. When the larvae hatch, they are just the size of a grain of rice. From the thousands of eggs, only 1 to 2 will survive to become mature octopuses.

This species is considered the most intelligent invertebrate with a complex, lobed, and folded brain.

While octopods typically exhibit shy behavior towards humans, there have been multiple diver attacks recorded. Diver attacks usually occur when the octopus is aggravated or provoked by humans, whether by accident or when trying to capture footage. Divers should use caution around the giant Pacific octopus because of its ability to inject venom into a bite through its saliva.

The octopus will typically stalk and trap its prey, but wait to eat until it returns to its den, leaving bones and shell remnants at the entrance. The giant Pacific octopus can catch multiple prey items at once, holding onto each one using the suction discs on their tentacles.

The giant Pacific octopus feeds on prey that live near the bottom of the ocean. It hunts a wide variety of crustaceans and mollusks such as clams, mussels, crabs, and fish.

Photo by Peggy Coburn.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Hooded Nudibranch Facts

With its clear coloration, round-shaped hood, and wispy tentacles, the hooded nudibranch (Melibe leonina) looks like a jellyfish but is actually a sea slug. They can grow to be about 3 to 4 inches long and are characterized by an imposing hood which is lined with inward-facing, short tentacles. The oral hood is used as a net to catch prey and help them to move through the water. The hooded nudibranch can often be found living in eelgrass meadows, a habitat that provides them with food and shelter from prey.

DID YOU KNOW?

Hooded nudibranchs catch their prey using a similar method to that of a Venus flytrap. They typically plant themselves on a blade of eelgrass, and as the grass sways, use their inflated hood to catch food, rapidly closing it when unknowing prey drift in.

Unlike most nudibranchs, the hooded nudibranch feeds on moving prey in shallow waters such as zooplankton, small crustaceans, and very small fish. Most other sea slugs typically go after immobile prey that lives in deeper waters.

Predators of the hooded nudibranchs are sunflower sea stars and crabs.

The name “nudibranch” is Latin for “naked gills.” Hooded nudibranchs have exposed gills that help them absorb oxygen in the water.

Photo by Vlad Karpinsky (Creative Commons Flickr). Banner photo by Peggy Coburn.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

FURTHER READING

Moon Jellyfish Facts

Moon jellyfish (Aurelia labiata) are small, translucent invertebrates that inhabit the northeast Pacific Ocean and frequent the waters of the Salish Sea. They can be distinguished by four opaque half-circles on a bell and a 16-scalloped bell margin. Unlike most jellyfish, their tentacles are thin and short, extending around the circumference of the bell. These jellyfish can be seen throughout the summertime in the Salish Sea floating near the surface where the temperature of the water is warmer. They usually gather in large masses in harbors and coves. Moon jellyfish eat fish eggs and larvae, zooplankton, small crustaceans, and cladocerans, known as water fleas.

DID YOU KNOW?

Moon jellyfish are closely related in looks and genome to Aurelia aurita, another species of moon jellyfish commonly found in the Atlantic Ocean.

Moon jellyfish have a short lifespan, usually emerging in early spring, then spawning and dying by late summer or early fall.

In the Salish Sea, the highest concentrations of jellyfish are observed during the month of June. The moon jellyfish and the lion’s mane jellyfish are the most frequently sighted species.

Young moon jellyfish are called polyps and tend to attach to the undersides of docks where they can avoid predators and have ample room to grow. Millions of polyps can be attached to the underside of a dock at one time.

Jellyfish are viewed as a nuisance when unpredictable blooms spawn great quantities of jellyfish at once. Their high numbers can cause them to congest fishing nets, and even clog and shut down power plants. Studies have shown that jellyfish populations increase rapidly in warmer temperatures.With climate change raising oceanic temperatures, we may encounter even larger outbreaks of jellyfish around the world.

Photo by Bruce Kerwin. Banner photo by Ume-y (Creative Commons Flickr).

Sand Lance Facts

The humble sand lance (Ammodytes personatus) is a small, silver forage fish that plays an important role in the ecosystem’s food web. Staying true to its name, the sand lance is known for burrowing face-first into the sand on the seafloor. In recent years, conservation efforts have been made to protect the sand lance population and their habitat. Protecting this population helps to conserve the variety of birds, fish, and mammals that eat them by keeping their food source viable.

DID YOU KNOW?

Not quite at the bottom of the food chain, the sand lance grows by feeding on plankton. Once the sand lance has fattened up, it becomes prey for Chinook salmon, which in turn are prey for the Southern Resident Killer Whales.

Up to 20 sand lance can fit in the beak of a tufted puffin while they are fishing underwater.

Sand lance are widely distributed through the Salish Sea and play a critical role in the food chain.

While they are able to bury themselves in varying kinds of sand from gravel to fine sand, they favor coarse sand allowing them to break through rapidly and breathe comfortably, even while buried underneath.

When the sand lance isn’t searching for plankton to eat, they spend most of their time in the seabed hiding from predators and waiting for their next opportunity to feed.

Photo by Mandy Lindeberg. Banner photo by David Ayers.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

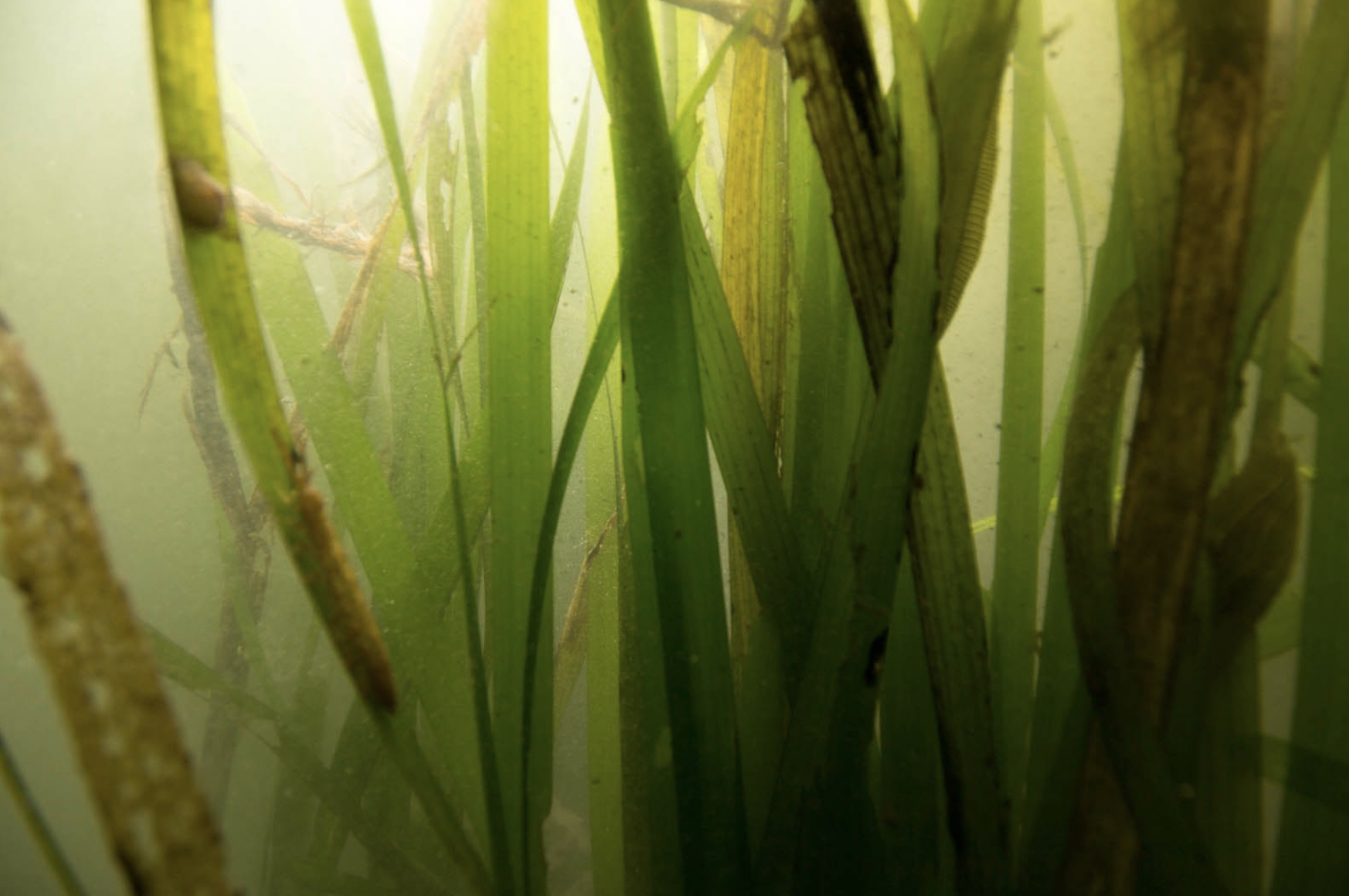

Eelgrass Facts

In some places around the Salish Sea you can find a beautiful brightly-colored green grass called eelgrass (Zostera marina) that lives in the intertidal and shallow subtidal zone. Like kelp, it provides a habitat for many organisms that use it for food and shelter. The health of the Salish Sea relies on not losing any of our eelgrass as this important habitat serves as a breeding ground and nursery for fishes and invertebrates.

DID YOU KNOW?

Eelgrass blades are thin and narrow, growing up from the sea floor toward the sun. In the greater Puget Sound, the optimal depth for eelgrass beds is between 0 and 2 meters deep.

Eelgrass is home to many organisms, such as Dungeness crabs, hooded nudibranchs, and fish such as juvenile Chinook salmon, Pacific herring, surf smelt, and many other species

Eelgrass is a carbon sink that makes up 10% of the ocean’s ability to store carbon. If you want to hear what photosynthesis sounds like underwater, a hydrophone can amplify the sound of eelgrass photosynthesizing as it absorbs greenhouse gases and emits oxygen, creating a rhythmic bubbling sound.

Eelgrass is highly susceptible to human-caused threats. Eelgrass can be damaged by pollutants, shading from docks and structures, anchors dropped on meadows, and more recently, eelgrass wasting disease which is caused by the pathogen Labyrinthula zosterae.

Photo by Eric Heupel (Creative Commons Flickr). Banner photo by Pat O’Hara.

Get more species facts with our free monthly newsletter!

Bull Kelp Facts

Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) is vital to the health of marine ecosystems because it provides a healthy variety of biodiversity. Kelp forests provide numerous animals with nutrients and habitat, including kelp crabs, red sea urchins, kelp greenling, kelp perch, and Pacific herring. Found along the coast from Alaska to central California, bull kelp uses a holdfast to anchor itself to rocks on the seafloor while a stalk grows towards the surface, reaching for rays of sunlight. The upper part of the stalk is a gas-filled float that enhances exposure to sunlight and promotes photosynthesis. This structure allows for the long, flat blades to sway in the current.

DID YOU KNOW?

Marine snails and kelp crabs consume kelp, but neither are quite as voracious as sea urchins. Urchins have been known to consume great quantities of kelp very quickly, completely decimating once-flourishing ecosystems. Because kelp is both a home and a source of nutrients for many species, their absence can cause other marine life to disappear as well.

Bull kelp dies in the winter and only produces one stipe and several blades in its lifespan. However, the blades are reproductive and the plant itself will produce trillions of zoospores for propagation in the future.

Bull kelp is an annual seaweed, meaning it grows from a spore to maturity in a single year. It can reach heights of up to 30 m (about 100 ft) and grow at a rate of up to 25 cm (about 10 in) per day! While bamboo (subfamily Bambusoideae) still hold the record for fastest growth in a single day - up to 100 cm (about 40 in) per day - bull kelp is still one of the fastest-growing plants around.

Sea star wasting syndrome has caused declines in sunflower sea star populations, causing a cascading effect on kelp forests. Without the sunflower sea stars to keep the sea urchin populations in check, these spiny creatures can clear cut bull kelp forests.

Photo by Caleb Slemmons (Creative Commons Flickr). Banner photo by Florian Graner.