By Bob Friel

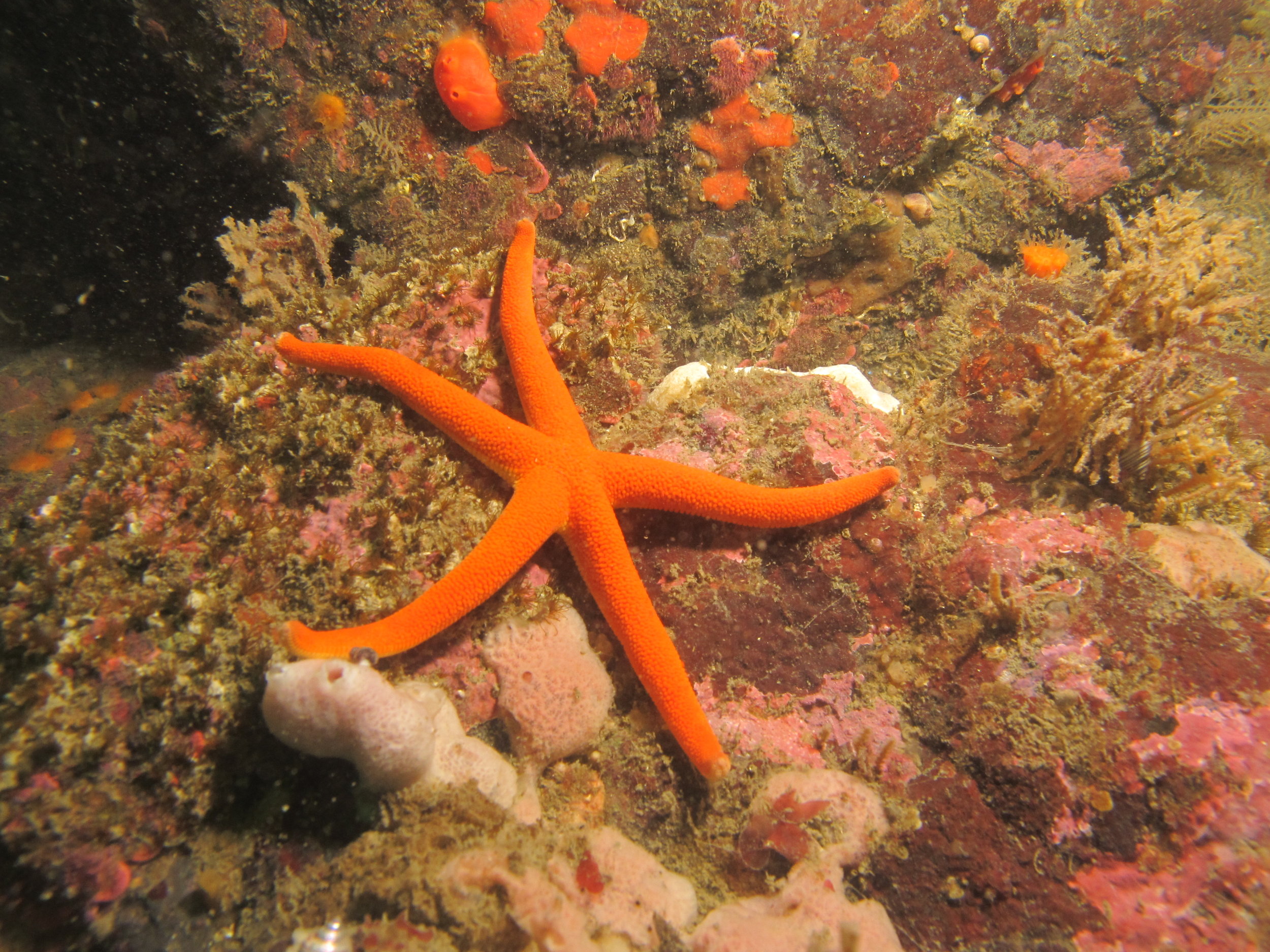

One of the largest marine wildlife disease epidemics ever known to science —Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD)—has not spared the Salish Sea. While the most visible effect of the epidemic so far has been the loss of thousands of ochre stars, the Crayola-colored shallow-water species that turn our tide pools into works of purple and orange art, SeaDoc has discovered that great ecological damage is happening in deeper water too.

Drawing on data from more than 8,000 REEF (Reef Environmental Education Foundation) surveys by trained scuba diving citizen scientists along with precise transect studies completed by certified scientific divers, we found that SSWD has decimated populations of the once abundant sunflower sea stars to the point they’re considered virtually extirpated throughout our inland sea.

The Salish Sea hosts a great galaxy of sea stars encompassing a remarkably diverse collection of species. Among those, the sunflower (Pycnopodia helianthoides) holds a special place. Familiar to crabbers who often found them stuffed inside their pots eating their bait, and to divers who commonly swam over bottoms literally crawling with them, before the epidemic began in 2013, sunflowers were the most abundant sea star found below the low-tide mark.

The majority of our sea stars are predators, but the sunflower is a carnivore on a whole other level of dominance. Huge, relatively fast, and with three octopuses’ worth of hydraulic-powered arms, it’s the sucker-footed Starasaurus rex of the subtidal kingdom. While most marine life—as well as drysuited divers—steer well clear of sea urchins and their long, prickly spines, the sunflower stars gobble them like candy and then spit out the spiky bits. It’s the loss of such a voracious urchin-eater that’s particularly disturbing when we consider SSWD’s effects on our local ecosystem.

Herbivorous urchins graze on algae. A previous marine epidemic that killed off urchin populations in Florida and the Caribbean allowed algae to overgrow corals and severely damage tropical reefs. In our temperate waters, the concern is the reverse happening: with fewer sea star predators around, the urchin numbers can explode like underwater locusts and decimate the algae, mowing down our vital kelp forests, leaving behind what are known as urchin barrens.

With kelp such a crucial source of food and habitat for so many other creatures, the worry is that the loss of sunflower sea stars, which we’ve learned are particularly susceptible to SSWD, could start a trophic cascade that negatively alters the Salish Sea ecosystem.

SeaDoc and our partners remain on the case as this epidemic continues to affect our waters. We’re continuing the basic critter-counting science that alerts us to changes in the environment, investigating the virus linked to SSWD, and trying to determine whether other environmental factors played a part in the outbreak. If it turns out that intervention is necessary, we’ll be there to provide the science critical to inform the decision-making.

- Read a PLOS One interview with Dr. Joe Gaydos about the study.

- Read the full publication.