These news items are from before October of 2013.

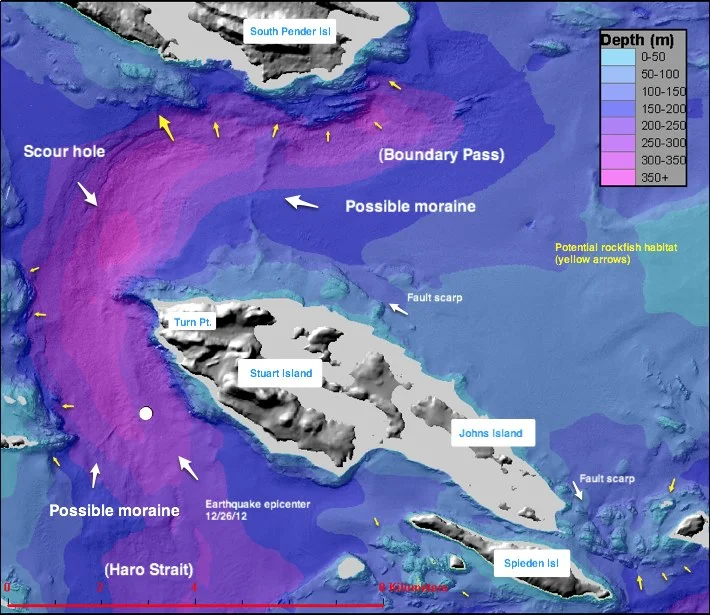

Habitat protection proposed for endangered rockfish in Puget Sound

Kitsap Sun, August 6, 2013

Nearly 1,200 square miles of Puget Sound has been proposed as critical habitat for three endangered species of rockfish. Joe Gaydos is quoted as saying, "It is a joy to see [proposals like this] coming out because it means we are moving forward." He added, "To have both the federal and state groups working on this collaboratively is itself a small success story, because we don't always see things go this smoothly."

Harbor porpoises now a common sight in Puget Sound

Seattle Times, July 8, 2013

According to the SeaDoc Society’s Joe Gaydos, harbor porpoises are one of the few cetaceans that are a resident of the Salish Sea year round. A decline in gill-net fisheries and increased cleanup of industrial pollution may be a factor in their recovery. As the population has risen, so have strandings. “Is that just because the population is increasing?” Gaydos asks in the Times piece. “Or is there something else going on? If they are dying of something and we are missing it, that is really serious. And we don’t have enough data to tell us that.”

Starting up the Harbor Seal pupping season

Islands Sounder, June 24, 2013

Our summer interns contributed an article on stranded harbor seal pups and the work of the Marine Mammal Stranding Network to the local paper on Orcas. Also in the San Juan Islander.

Killer Whale strandings reveal much about health of species

Vancouver Sun, June 7, 2013

Larry Pynn covered our paper on Killer Whale strandings. Also covered on Phys.org, NewsPoint Africa, Huffington Post Canada, Nature World News, CBC.ca, Yahoo! Canada News, GlobalNews.ca, Victoria Times Colonist, The Province, Leader Post, Truro Daily News, Journal Pioneer, e! Science News, Bright Surf, Science Codex, Alaska Native News, Science Blog, the Globe and Mail, Futurity.org, and others. Joe Gaydos was interviewed on CHEKnews.ca.

Vanquishing zombie fishing nets in Puget Sound

EarthFix, May 21, 2013

Ashley Ahearn reported on the Northwest Straits Foundation's efforts to remove derelict fishing gear from the Salish Sea. The article referenced the SeaDoc Society's work to analyze how much revenue is lost from bycatch in derelict nets.

Saving sea lions in distress goal of workshop at Vancouver Aquarium

Times Colonist, May 21, 2013

Judith LaVoie covered a sea lion disentanglement workshop that SeaDoc participated in. The article featured quotes from Vancouver Aquarium veterinarian Marty Haulena, who serves on the SeaDoc science advisory board.

The mysterious decline of Puget Sound herring

Crosscut, March 27, 2013

Lisa Stiffler writes about the importance of herring to the Puget Sound ecosystem. Joe Gaydos quoted on the connection between declines in Western grebe populations and Cherry Point herring stocks.

Joe Gaydos interviewed on Good Morning America about killer whales trapped in ice

Good Morning America, January 10, 2013

When a group of 11 killer whales were trapped in the ice in northern Canada, Good Morning America called Joe Gaydos by Skype for comments. (After the whales got to freedom, GMA released a revised video that no longer features Joe, but his quotes are still in the body of the article.)

Rehabilitated seals exhibit wanderlust: Transmitters on wild specimens show they tend to stick closer to home

Vancouver Sun, December 30, 2012

Larry Pynn of the Vancouver Sun wrote about SeaDoc's study of 10 wild and 10 rehabilitated harbor seal pups. The study showed significant differences between the two cohorts. Pynn also discussed a separate study of rehabilitated seals undertaken by the Vancouver Aquarium.

Human Values Count in Puget Sound Recovery

Kitsap Sun, November 24, 2012

Christopher Dunagan of the Kitsap Sun wrote about the importance of indicators of human health and well-being in the work of the Puget Sound Partnership. Joe Gaydos, as chair of the PSP's Science Panel, is quoted discussing the importance of setting up indicators that track the underlying health of the sound, such as plankton biomass. (Joe's comments are at the bottom of the article)

Massive Octopus Among the Wonders of the Salish Sea

Everett Herald, October 14, 2012

Sharon Wootton of the Herald wrote about octopuses, anemones, and other extraordinary animals of the Salish Sea, with extensive quotes of Joe Gaydos.

Achievement of grand proportions

Islands Sounder, August 22, 2012

The Sounder marked the 1,001st spay/neuter performed by Dr. Joe Gaydos at the Orcas Animal Shelter since he started working there in 2003. Joe does one 3-hour shift a week, most weeks. The article also highlighted SeaDoc's summer interns, Christine and Karisa, who have also assisted at the shelter this summer.

Mapping the Underwater Wonderland of the Salish Sea

Seattle Times, July 25, 2012

Lynda Mapes of the Seattle Times wrote about SeaDoc's underwater habitat mapping lab.

Stranded Seal Pups are Being Tagged, Monitored

Islands Sounder, July 16, 2012

SeaDoc interns Karisa Tang and Christine Parker were featured in a story about seal pup stranding. This year the rescued pups are being tagged with little hat tags in addition to flipper tags for easier identification from a distance. The tags are glued onto the pups' hair and will fall off when the pups molt.

Defenders of the Salish Sea

UC Davis Magazine, July 2012

The UC Davis alumni magazine recently featured SeaDoc in a piece titled "Defenders of the Salish Sea." The article succinctly tells the story of SeaDoc and has generated a bunch of interest in SeaDoc from UC Davis alumni in Washington State and around the world. Check it out for yourself or email it to a friend.

Looking for Kinks in the Food Web

Kitsap Sun, June 17, 2012

Christopher Dunagan wrote a detailed piece about the importance of forage fish and research into the shoreline processes that enable them to thrive. He quotes Joe Gaydos, ""We are just starting to make the bridges between shoreline processes and the impacts on marine life," Gaydos said. "Are salmon going to have enough food as time goes on? There is a lot for us to learn.""

What Killed Orca Victoria? Some Point to Naval Tests

NPR All Things Considered, May 16, 2012

Earthfix's Ashley Ahearn reported for NPR on the investigation into L112's death. (Just to be clear, Joe Gaydos is not suggesting Navy involvement at this time.)

Report Inconclusive on What Killed Orca L112

EarthFix/KUOW, May 15, 2012

Earthfix's Ashley Ahearn interviewed Joe Gaydos for a story on the investigation. The story, titled "Report Inconclusive on What Killed Orca L112" quotes Joe acknowledging that it's challenging for everyone that they can't yet pinpoint a cause of death.

Puget Sound Science Panel completes two-year plan

Kitsap Sun, May 4, 2012

Christopher Dunagan interviewed Joe Gaydos in his role as chair of the Puget Sound Partnership Science Panel. “We want to know everything, of course,” chairman Joe Gaydos told me. “But just because there’s a gap in our knowledge does not mean we should go out and do a study. The real question is, where does the lack of science hinder our ability to make decisions? We’re not just doing science for science’s sake but to help us make better decisions.”

Coastal Waterbirds in B.C. Slipping Away

Vancouver Sun, April 19, 2012

Reporter Larry Pynn wrote about the declines in marine bird species, and referred to SeaDoc's ongoing marine bird study by Nacho Vilchis.

Marine Mammals Coming Back

Vancouver Sun, April 19, 2012

Reporter Larry Pynn tracked the recovery of many marine mammal species, and balanced it against species that are not recovering well. Pynn referred to the SeaDoc study of Species of Concern that found 113 species that were listed or candidates for listing as threatened or endangered.

Experts sleuth out what killed Puget Sound orca

Huffington Post via Associated Press, April 12, 2012

"Joe Gaydos, a wildlife veterinarian with SeaDoc Society who has been working with a team of experts to understand what killed the whale, said they're considering all possible scenarios, including a strike from another animal, sonar activity, an explosion and other possibilities.

'Right now everything is on the table,' he said, adding that 'as scientists, we have to weigh all the evidence before we come to a conclusion.'

Gaydos and a team of biologists dissected the orca's head and examined the skull and brain during a necropsy last month. They found no fractures of the skull or jaw, indicating that the trauma or the force was dispersed over a larger area and not likely caused by a boat strike. They also found hemorrhaging and bleeding in the back of the orca's head.

'When something is shaken up, you'll have trauma at multiple locations,' Gaydos said."

Keynote address at Sound Waters examines impact of marine science

South Whidbey Record, January 24, 2012

"Gaydos will explain how science is not a panacea, but it can and does play an important role in efforts to design a healthy ecosystem. The presentation will examine the merits and limitations of science while proposing realistic options for citizens to participate in, understand and use science as efforts continue to improve the health of the Salish Sea."

UC Davis Veterinarian Elected Chair of Science Panel for Major Ecosystem Restoration Effort

Good News For Pets, January 7, 2012

Also published at http://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/whatsnew/article.cfm?id=2487.

SeaDoc's Western Grebe tracking project covered in Argos Forum magazine

Argos Forum #73, December 2011

Kyra Mills-Parker of the Oiled Wildlife Care Network at UC Davis covered the Western Grebe transmitter project in an article entitled, Oil and Seabirds Don't Mix: New Techniques for Tracking Western Grebes After Oil Spills. Download the PDF. Here's the link to the publication of the surgical technique: Short-term survival and effects of transmitter implantation into Western Grebes using a modified surgical procedure.

SeaDoc Society director Joe Gaydos elected chair of Puget Sound Partnership Science Panel

Islands Sounder, December 20, 2011

SeaDoc Society regional director Joe Gaydos has been elected Chair of the Science Panel of the Puget Sound Partnership, the Washington State agency charged with restoring Puget Sound by 2020.

Salish Sea pH is dropping as carbon dioxide levels rise

Islands Sounder, December 5, 2011

The Sounder covered research into ocean acidification funded by the SeaDoc Society. Meredith Griffin's article explains what this research means and how to understand it. She quotes SeaDoc scientist Ignacio Vilchis: "What long-term effects in response to these drops in pH mean for ocean life is the million dollar question, but we are certain that some shelled organisms are going to be affected."

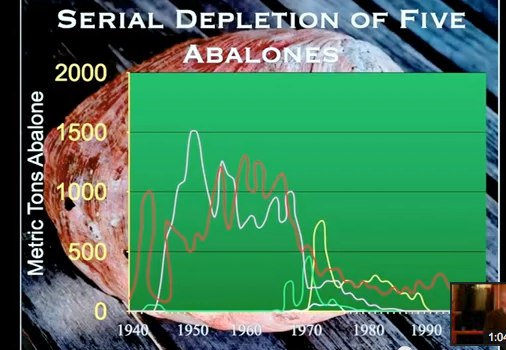

Abalone Research

Islands Sounder, Nov. 25, 2011.

The Islands Sounder covered the publication of abalone research funded by SeaDoc.

Derelict Gear in California

San Jose Mercury News, Oct 31, 2011.

SeaDoc executive director Kirsten Gilardi was quoted in a Mercury News article about derelict fishing gear in Monterey Bay.

"We've seen a lot of beautiful rocky reef habitat covered in nets. They essentially smother the reefs," said veterinarian Kirsten Gilardi, associate director of the Wildlife Health Center at UC Davis. "They just drape over the reef like big bags," she said. "The kind of animals that are supposed to live there can't. The things that fish feed on can't grow. We've even found tires and old toilets dumped on a reef a couple of miles offshore off Malibu."

In 2007 and 2008, UC Davis researchers removed more than 1 million feet of fishing line and thousands of hooks from the waters around 15 piers between Santa Cruz and Imperial Beach. They also left recycling containers for old plastic fishing line on the piers, but grants to do more cleanup work ran out.

So far, researchers have found that Monterey Bay contains far less debris than waters off Southern California and nearshore waters around piers. In Southern California and other places, the gear actually continues to catch fish, lobsters, crabs and other species, a practice known as "ghost fishing."

Species of Concern Almost Double

The 2011 Species of Concern paper written by Joe Gaydos and Nick Brown, and presented by Brown at the Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference, showed that the total number of species of concern has jumped from 64 in 2008 to 113 by January of 2011. The story was picked up by the Associated Press (by environmental reporter Phuong Le) and reprinted widely in outlets like the Seattle Times, Bellingham Herald, Kitsap Sun, several local television channels

Other publications on this topic include Meredith Griffin's piece in the Islands Sounder, and Curtis Cartier's piece in the Seattle Weekly, where he quoted Joe Gaydos: "Still, Gaydos says that economics is a crucial point to remember when thinking about the importance of species preservation. 'Wildlife watching employs about 21,000 people in Washington state,' he says, citing Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife numbers. 'That might not be more than Boeing, but it's more than Microsoft.'"

Elk at Mount St. Helens

Oregon Public Broadcasting, October 2011

Joe Gaydos was the support vet for some of the elk operations featured in this video and appears a couple of times. Note: this work is not funded by SeaDoc and Joe's time was paid for by the agencies involved. Video here.

SeaDoc interns monitor elephant seal stranded at West Beach

Islands Sounder, August 30, 2011

SeaDoc's summer internship program was featured in an article in the Islands Sounder by Meredith Griffin. The article covered the interns' response to a possible stranding of an immature male elephant seal. In addition to responding to marine mammal strandings as part of the Marine Mammal Stranding Network, the interns, who are third-year veterinary students, also do weekly necropsies on dead mammals.

Born to be wild: Rehabbed and wild seal pups behave differently

Seattle Times, August 3, 2011

Lynda Mapes wrote about preliminary results from SeaDoc's tracking study of wild-weaned and rehabilitated harbor seal pups.

"We were blown away," said Joe Gaydos of the SeaDoc Society, a non-profit research and conservation society based on Orcas Island. "It was pretty dramatic, we were amazed to see that those guys don't behave like wild seals."

"It is as if you had a group of people go out for a walk, and half of them go too far. Why?" Gaydos said. The researchers' hypothesis is that the rehab seals missed out on three or four weeks of instruction from their mothers, in which they would have leaned how to hunt by watching her, even though they would have still been nursing.

Barnacle-nibbling bears: New Salish Sea checklist links land & sea

Seattle Times, July 5, 2011

Joe Gaydos and SeaDoc were featured in an article by Sandi Doughton on the Field Notes blog.

"If you want to restore an ecosystem, it's really important to know what is there, or what has been there historically," said Joe Gaydos, SeaDoc's Orcas Island-based regional director.

Salish Sea Change

Canadian Geographic, June 2011

Joe Gaydos provided background for an article by Isabelle Groc on how the name change from the Puget Sound/Georgia Basin area to the Salish Sea is important for conservation efforts.

Puget Sound Partnership steadfast in science-based solutions to environmental threats

Kitsap Sun, February 5, 2011

Christopher Dunagan wrote about the Puget Sound Partnership and quoted Joe Gaydos extensively on the role of the Science Panel.

Since its inception, the partnership has struggled with what it means to restore Puget Sound to health by the year 2020 — a goal promoted by Gov. Chris Gregoire. Many people wanted the Science Panel to provide the answer.

But there is no single answer, said Joe Gaydos, a veterinarian with the SeaDoc Society who serves as vice chairman on the Science Panel.

"There are degrees of health, as it is with people," he said. "For some people, that means being able to run a four-hour marathon. For others, it means walking down and getting the mail. As scientists, we can tell you that if you want to run a four-hour marathon, you need to do this and this and this. If you want to get the mail, you have to do this."

A child may like killer whales and wish there would be 500 of them in Puget Sound, he said, but scientists can tell from the number of females and their reproductive capacity whether that is possible. Science can help identify factors, such as food and habitat, needed to reach ecological goals.

What will it take to restore salmon populations? What creatures would be helped by restoring an extra three miles of eelgrass or removing dams or dikes? Given budget limitations, the questions need to be carefully considered, Gaydos said, and that takes a partnership between scientists and policymakers.

Baby seals saved, returned to wild — then what? Scientists now track them

Seattle Times, October 25, 2010

Linda Mapes wrote about rehabilitation efforts for stranded and abandoned harbor seal pups, and the study, run by SeaDoc with funding from the National Marine Fisheries Service, that aims to find out whether rehabilitation efforts are successful.

Joe Gaydos is quoted discussing the role that abandoned pups might play in the ecosystem. "They have big eyes and big whiskers, and they are cute," said Joe Gaydos, regional director and chief scientist for the SeaDoc Society, a nonprofit science and conservation group that is leading the study. Nobody, he noted, has much appreciation for the predators [the seal pup] might feed, if left to die on the beach. "We don't remember that they are supposed to feed some eagle's baby, or some crabs."

State board adds Salish Sea to region's watery lexicon

Seattle Times, October 31, 2009

Lynda Mapes wrote about the approval of the "Salish Sea" as a name for the inland waters of Washington State by the Washington State Board on Geographic Names. (Approval for this also came shortly afterward from the US Board of Geographic Names and its counterpart in Canada.)

Mapes wrote: Advocates of the name celebrated Friday. "It's an ecological victory," said Joe Gaydos, chief scientist for the SeaDoc Society, a nonprofit marine-science group that has used the name for years. "We talk about place-based conservation, but how do you do that without a name for the place or a sense of place? The border doesn't mean anything for the killer whales and the Pacific salmon that cross it every day."

Beyond Puget Sound: Ten ideas for saving the Salish Sea

Seattle Times, March 26, 2009

In a guest column for the Seattle Times, Joe Gaydos wrote about the solid foundation of ecological principles that can be used for designing a healthy ecosystem. (It's a great introduction to the underlying philosophy of the SeaDoc Society.)

Puget Sound Research Conference Begins Monday

Kitsap Sun, February 8, 2009

Christopher Dunagan's article highlights the Salish Sea Science Prize, awarded in 2009 to Ken Balcomb, who pioneered the photo identification of killer whales. The population information from Balcomb's annual census "has proved invaluable in understanding orca longevity and the effects of disease and toxic chemicals on the population, said Joe Gaydos, regional director of the SeaDoc Society. The census was the basis of an analysis that led to the listing of the killer whales as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. "Ken's life work has been scientifically rigorous and has fundamentally changed the way we think about killer whales and marine wildlife," Gaydos said. "He really epitomizes the intent of the award.""

Scientists Discuss Salmon Runs in Wake of Orca Deaths

Kitsap Sun, November 18, 2008

Christopher Dunagan covered the "strategic convening" moderated by Joe Gaydos to bring together fisheries and marine mammal biologists, oceanographers, toxicologists and behavior biologists to discuss the deaths of 7 killer whales in 2008.

Dead Orca Calf Could Provide Answers

Kitsap Sun, August 5, 2008

Christopher Dunagan's article describes the stillborn orca calf found on Henry Island and the information about the animal's toxic burden that might be gleaned from a forthcoming necropsy.

Planning Could Save More Birds Caught in Oil Spills

Kitsap Sun, March 29, 2008

After the Nov 2007 Cosco Busan spill in San Francisco Bay, Washington State rushed to improve its planning for oil spill response. Christopher Dunagan quoted Joe Gaydos: "In San Francisco, they were prepared," said Joe Gaydos, a veterinarian and regional director of the SeaDoc Society on Orcas Island. "They have been working on this for many years, and it kind of brought the message home."

Grebe Experiment on Road to Success

March 22, 2007

Christopher Dunagan wrote about surgical procedures developed with Western grebes from the Kitsap Peninsula that could help save the species. Joe Gaydos is quoted extensively. (Note: future work with the same surgical technique made possible the 2010/2011 grebe tracking study by SeaDoc.) Also see: Solving the Mystery of the Missing Birds, a March 5, 2007 article by Dunagan about the capture of the Western grebes.

Although the harbor porpoise is the most abundant and widely dispersed cetacean species in the Salish Sea, we still know very little about its habitat needs, distribution, population trends, life cycle, genetics, behavior and role in the ecosystem.

Harbor porpoises feed primarily on fish and are among the smallest of the cetaceans, reaching an average size of about 5 feet and 120 pounds. They can dive deep, more than 655 feet, but usually stay near the surface, coming up regularly to breathe with a distinctive puffing noise that resembles a sneeze.

Although the harbor porpoise is the most abundant and widely dispersed cetacean species in the Salish Sea, we still know very little about its habitat needs, distribution, population trends, life cycle, genetics, behavior and role in the ecosystem.

Harbor porpoises feed primarily on fish and are among the smallest of the cetaceans, reaching an average size of about 5 feet and 120 pounds. They can dive deep, more than 655 feet, but usually stay near the surface, coming up regularly to breathe with a distinctive puffing noise that resembles a sneeze.

EASTSOUND, Wash. — "Watch out for the otter scat," warns UC Davis wildlife veterinarian Joe Gaydos, as he points to several tidy pink-crustacean-tinged piles on a dock. A glance over the edge of the dock reveals a world of anemones and algae swaying in the incoming tide. And overhead, a pair of courting bald eagles circles above the cedars in a gray February sky.

EASTSOUND, Wash. — "Watch out for the otter scat," warns UC Davis wildlife veterinarian Joe Gaydos, as he points to several tidy pink-crustacean-tinged piles on a dock. A glance over the edge of the dock reveals a world of anemones and algae swaying in the incoming tide. And overhead, a pair of courting bald eagles circles above the cedars in a gray February sky. River otters Those telltale signs of otters on the dock provide evidence for a scientific study on how the predators, which eat up to 15–20 percent of their body weight in food every day, could affect salmon and rockfish populations.

River otters Those telltale signs of otters on the dock provide evidence for a scientific study on how the predators, which eat up to 15–20 percent of their body weight in food every day, could affect salmon and rockfish populations. Killer whales Three distinct types of killer whales, or orcas (Orcinus orca), live in the Salish Sea. The most commonly encountered are the fish-eating "resident" orcas. These whales are salmon eaters, preferring Chinook, as shown in recent studies. Less commonly seen are the marine mammal-eating "transient" killer whales. Occasionally, "offshore" killer whales are spotted in the Salish Sea and are thought to be fish and shark-eaters. All three ecotypes of killer whales are state and federally listed as endangered.

Killer whales Three distinct types of killer whales, or orcas (Orcinus orca), live in the Salish Sea. The most commonly encountered are the fish-eating "resident" orcas. These whales are salmon eaters, preferring Chinook, as shown in recent studies. Less commonly seen are the marine mammal-eating "transient" killer whales. Occasionally, "offshore" killer whales are spotted in the Salish Sea and are thought to be fish and shark-eaters. All three ecotypes of killer whales are state and federally listed as endangered.

Dioxins and furans are highly toxic persistent organic pollutants that once were dumped into the Salish Sea in pulp mill effluent. They are counted among the twelve most poisonous “dirty dozen” toxins in the world, and once were concentrated in fish and fish-eating birds in British Columbia, causing fishery closures and waterfowl consumption advisories. Thanks to mandated changes in bleaching processes and restrictions on usage of the parent compounds for these toxic chemicals at pulp mills, discharge of dioxins and furans into the Salish Sea has been eliminated.

Dioxins and furans are highly toxic persistent organic pollutants that once were dumped into the Salish Sea in pulp mill effluent. They are counted among the twelve most poisonous “dirty dozen” toxins in the world, and once were concentrated in fish and fish-eating birds in British Columbia, causing fishery closures and waterfowl consumption advisories. Thanks to mandated changes in bleaching processes and restrictions on usage of the parent compounds for these toxic chemicals at pulp mills, discharge of dioxins and furans into the Salish Sea has been eliminated. Dr. Elliot began his work in the mid-1980s with research on great blue herons, to better understand the possible effects of persistent organic pollutants on these aquatic birds. As part of a team that included population biologists, chemists and biochemists, Elliot documented for the first time the exposure of wild birds to the forest industry derived pollutants, dioxins and furans. As well, he documented high concentrations of these chemicals in bald eagles living near pulp mill sites, and went on to determine the deleterious effects of these toxins on eagles breeding near contaminated areas. His initial studies led to further research demonstrating the effects of these chemicals on embryonic development of both herons and cormorants at colonies near pulp mills and other forest industry sites in the Salish Sea.

Dr. Elliot began his work in the mid-1980s with research on great blue herons, to better understand the possible effects of persistent organic pollutants on these aquatic birds. As part of a team that included population biologists, chemists and biochemists, Elliot documented for the first time the exposure of wild birds to the forest industry derived pollutants, dioxins and furans. As well, he documented high concentrations of these chemicals in bald eagles living near pulp mill sites, and went on to determine the deleterious effects of these toxins on eagles breeding near contaminated areas. His initial studies led to further research demonstrating the effects of these chemicals on embryonic development of both herons and cormorants at colonies near pulp mills and other forest industry sites in the Salish Sea.