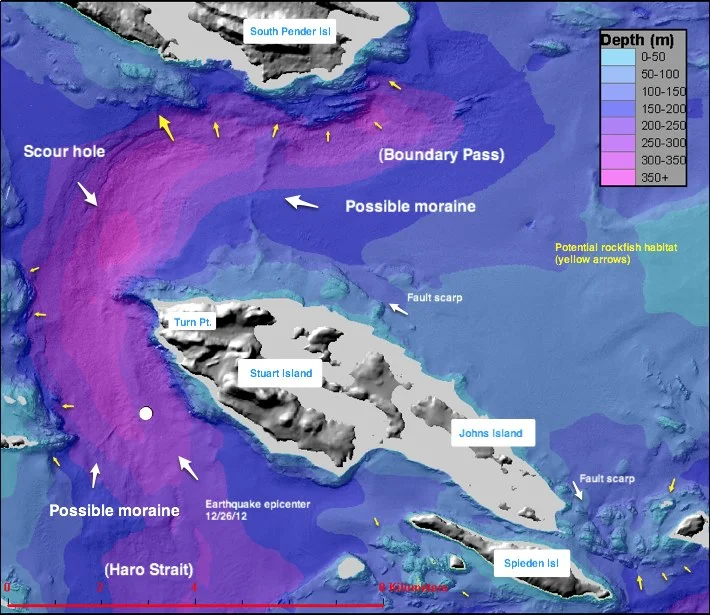

The point of a map is to help us get where we're trying to go. In this case, knowing the underwater geography of a place can help us choose where to focus our investigations and conservation efforts.

Salish Sea Marine Bird Project

Vilchis, L. I. C. K. Johnson, J. R. Evenson, S. F. Pearson, K. L. Barry, P. Davidson, M. G. Raphael, and J. K. Gaydos. 2014. Assessing Ecological Correlates of Marine Bird Declines to Inform Marine Conservation. Conservation Biology. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12378. (Open access publication)

Where have all the birds gone?

The last 30 years have seen precipitous declines in many of the bird species that visit the Salish Sea during the winter.

Using various tools, private money and strategic collaborations, SeaDoc made a substantial investment to understand the problem of declining marine birds. We recently completed research demonstrating that diving birds that eat schooling forage fish are the species most likely to be in decline.

Tackling such a big issue is not easy. Understanding how we worked through this issue gives you a good idea of how SeaDoc can address what might seem to be insurmountable obstacles to healing the Salish Sea. It also shows you how private support makes our work possible.

Step 1: Identify the information gap

In 2005, SeaDoc brought researchers and managers from the US and Canada together to talk about the state of marine bird populations in the Salish Sea. It became clear that we were facing a big problem. Birds were declining in different jurisdictions, but it wasn’t clear how steep the declines were, which species were involved or what factors were behind these declines.

Because no one took a big-picture approach, bird restoration efforts were focused on one species at a time. But was there something going on at the ecosystem level causing multiple species to be declining?

We realized we needed an ecosystem-level look at which species were in decline and why.

Step 2. Get around transboundary roadblocks

Decades worth of data had been collected in Washington and British Columbia by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), Audubon, and Bird Studies Canada. But the organizations used different survey techniques and geographic scales so people had not been able to look at the data to get a perspective for the entire ecosystem.

SeaDoc was the ideal group to take on the challenge of merging these differing data sets from two different countries. State, provincial, and federal governments rarely have the time for this kind of effort. Also they have political constraints and pressures that make it hard to see past their borders.

Step 3. Hire a scientist to do the work

Collaborating with multiple groups, merging complex data sets and analyzing decades of data is a full time job for several years. Stephanie Wagner, a woman who loved the Salish Sea and its creatures, made a legacy gift to SeaDoc before she died. This gift provided the funding that allowed us to hire Dr. Nacho Vilchis to lead this important work.

Step 4. Use an epidemiological approach

Dr. Vilchis' first task was to get the data sets to “talk to each other.” WDFW conducts aerial transects from a plane. Bird Studies Canada and Audubon use point counts. Both are good techniques, but they produce surveys that are difficult to compare.

Nacho, who has a background in the statistical manipulations of large data sets, found a way to combine and use the three surveys in one overall analysis. Then he trimmed the set down to just 39 core species, removing the occasional visitors and the birds for which he didn’t have enough data to draw robust conclusions.

He also used GIS maps of the Salish Sea to connect each data point not only to a geographical area but also to major habitat characteristics, such as water depth.

Drawing heavily on the “Doc” part of SeaDoc, we used an epidemiological approach to find a likely diagnosis. Just as the family doc quizzes you for risk factors for diabetes or heart disease, SeaDoc found that two lifestyle factors among seabirds correlated to a very high risk of population decline.

Step 5. Translate results into recovery

The work, published in the internationally-acclaimed peer-reviewed journal Conservation Biology, showed that birds that dive to find food are much more likely (11 times as likely) to be in decline compared to non-divers.

But it’s worse if you’re a diver on a restricted fish diet. Diving birds that focus their efforts on small schooling fishes called forage fish were 16 times as likely to be in decline. Forage fish are small schooling fish that convert plankton into fat and are eaten by other fish, birds and mammals. These include herring, smelt, anchovies, eulachon, sardines, and sand lance.

But publishing a paper is not the end. It actually is just the beginning. This paper is now being used by scientists, managers and policy makers as evidence for the need to recover marine birds. Recovering forage fish will not just benefit birds, however. Because forage fish turn plankton into fat that’s available for other animals, they are a key part of the ecosystem and their recovery will benefit salmon, lingcod, rockfish, harbor porpoise and many other species within the Salish Sea.

Four key factors made this project successful.

1. Good data

Dr. Vilchis could not have conducted this analysis without scientists and citizens having already spent decades collecting rigorous data. The collection of these data took money, persistence, and forethought.

2. Collaboration

From the beginning, this project has been a story of collaboration. From the individuals collecting data over two decades to the senior scientists who worked out a way to share their data, it’s taken the work of many people working in different jurisdictions to make this happen. Our collaborators shared three huge datasets collected on two sides of an international border. They only did so because they were confident that SeaDoc would be able to use the data to produce robust scientific results.

3. Working on the level of the ecosystem, not the politics

This was the first study to look at bird declines across the entire Salish Sea marine ecosystem.

Most Canadian or US maps stop at the border, but the Salish Sea does not. Too often, the mandates and responsibilities of the people who work at the various state, provincial, and federal agencies tasked with keeping wildlife populations healthy also stop at the border.

SeaDoc, being privately supported by people like you who understand how important it is to treat the ecosystem as a whole, works across the entire ecosystem.

4. An extraordinary legacy gift

In the end, one person's financial gift made this project possible.

Without Stephanie Wagner’s legacy gift, this project would have been just a good idea that never got done. Instead, we made it someone’s job to find the truth that was hidden in the data.

Stephanie Wagner’s thoughtful gift enabled us to point clearly to a hidden problem affecting the productivity of the entire Salish Sea ecosystem. With her gift we were able to do good science that will make a difference in how scientists and managers work on healing the Salish Sea.

Put plainly, money can change the world for the better.

Please contact SeaDoc or your financial advisor if you’re interested in including SeaDoc in your will so you can leave a legacy for the health of the Salish Sea.

Alien Invaders: Invasive tunicates and shellfish aquaculture

While headlines about invasive tunicates have at times reached the breathless pitch of ads for campy horror films, there was legitimate concern because invasive tunicates in other regions of North America have severely impacted the aquaculture industry. Our Pacific Northwest shellfish industry annually pumps millions of dollars into the local economy. Introduced tunicates could potentially cause ecological and financial disaster.

River Otter Diet and Predation Project

Video: Milton Love on Fishes of the Pacific Coast

On Tuesday, March 12, 2013, the irreverent Dr. Milton Love graced Orcas Island with an in-depth look at some of the fascinating fishes of the Salish Sea. Milton Love is the author of the 672-page book, Certainly More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast, and has published over 90 scientific publications on the fishes of the Pacific Coast. He will discuss highlights from this book and will entertain the audience with amazing facts and stories about fishes.

Video: Rockfish Recompression

The Understudied Harbor Porpoise

Although the harbor porpoise is the most abundant and widely dispersed cetacean species in the Salish Sea, we still know very little about its habitat needs, distribution, population trends, life cycle, genetics, behavior and role in the ecosystem.

Harbor porpoises feed primarily on fish and are among the smallest of the cetaceans, reaching an average size of about 5 feet and 120 pounds. They can dive deep, more than 655 feet, but usually stay near the surface, coming up regularly to breathe with a distinctive puffing noise that resembles a sneeze.

Although the harbor porpoise is the most abundant and widely dispersed cetacean species in the Salish Sea, we still know very little about its habitat needs, distribution, population trends, life cycle, genetics, behavior and role in the ecosystem.

Harbor porpoises feed primarily on fish and are among the smallest of the cetaceans, reaching an average size of about 5 feet and 120 pounds. They can dive deep, more than 655 feet, but usually stay near the surface, coming up regularly to breathe with a distinctive puffing noise that resembles a sneeze.

In the Salish Sea, harbor porpoises face a number of threats including pollution, noise, crowding, death due to bycatch, depleted stocks of forage fish, and habitat loss.

On February 7th, SeaDoc helped convene a US / Canadian workshop to bring scientists and managers together. This "think-tank," co-sponsored by the Pacific Biodiversity Institute and Cascadia Research Collective, identified areas where more data are needed to better understand and manage the population, including things like doing a population stock assessment that will tell us if their numbers have grown or declined since the last one was conducted a decade ago.

This workshop is a good example of how SeaDoc works to bring US and Canadian scientists together to improve our management of the ecosystem. It's a repeat performance on past successful SeaDoc "think tanks" focusing on rockfish, abalone and forage fish.

The meeting notes, including some consensus statements from the scientists involved, are available as a PDF. Click here to download.

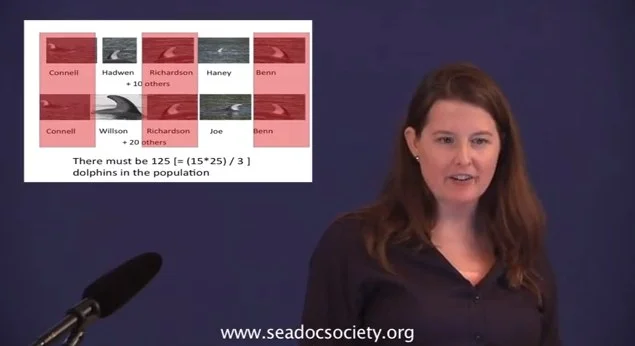

Video: Erin Ashe on Dolphins of the Pacific Northwest

Pacific White-Sided Dolphins, also known as “Lags,” a shortened form of their scientific name Lagenorhynchus obliquidens, are offshore schooling dolphins that are becoming more common in the Salish Sea. They’re fast, they jump and leap from the water, and like most cetaceans, they have amazingly large brains.

Video: Gary Davis: The Sea and Us - A Voyage of Discovery

Video: Leslie Dierauf on climate change, December 2012

Seals on the Run

Every summer, dozens of stranded baby harbor seals are brought to centers where they’re rehabilitated and released back into the wild. People expect these animals will behave like wild seals. But do they?

To find out, SeaDoc and colleagues satellite-tagged and tracked 20 harbor seal pups – half rehabilitated, half naturally weaned. The differences were big. Rehabilitated seal pups took off like torpedoes after release, traveling three times farther daily and dispersing three times as widely as the wild ones. And the rehabbed pups only transmitted signals for half as long as their wild cohorts, which could relate to how long they survived.

What’s extra fascinating here is that we’re talking about a mammal that spends just a single month nursing before it’s left on its own to survive. But if human-reared pups are traveling so much further, it could mean that wild pups actually learn quite a bit about foraging in the short time they spend flippering alongside their mothers, even if they’re only nursing and not catching fish. It could also mean that wild pups “imprint” on a local area during their first month. Or it might mean that rehabbed pups are naive to navigating the strong currents that sweep through the San Juans. It is time to learn how best to enhance rehabilitation techniques to get pups behaving more like wild seal pups after release.

More Information:

![]() SeaDoc's paper was written by Joe Gaydos and Ignacio Vilchis of the SeaDoc Society (UC Davis), Monique Lance and Steven Jeffries of the Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife, Austen Thomas of the University of British Columbia, Vanessa Greenwood and Penny Harner of Wolf Hollow Rehabilitation Center, and Michael Ziccardi of the Wildlife Health Center at UC Davis.

SeaDoc's paper was written by Joe Gaydos and Ignacio Vilchis of the SeaDoc Society (UC Davis), Monique Lance and Steven Jeffries of the Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife, Austen Thomas of the University of British Columbia, Vanessa Greenwood and Penny Harner of Wolf Hollow Rehabilitation Center, and Michael Ziccardi of the Wildlife Health Center at UC Davis.

The abstract is here. If you would like a copy of the full manuscript please email your request to seadoc@seadocsociety.org.

This study was funded by NOAA's John H. Prescott Marine Mammal Rescue Assistance Grant Program and private donations from SeaDoc supporters, including a significant donation from Bill and Lannie Hoglund. For this particular study, the private donations were a critical part of the mix because the Prescott funds could not be used to study wild-weaned seals.

Overview of post-rehabilitation research:

At the 2012 North American Veterinary Conference, Joe Gaydos gave an overview of the need for post-rehabilitation studies and reviewed the studies performed to date. He also discussed the role of veterinarians in marine mammal rehabilitation. Read the PDF.

Stranded seal recovery:

Stranded seals are generally found in the summer months. There are a number of reasons why pups become separated from their mothers, including illness, interference from dogs and humans, and maternal death. SeaDoc's summer interns assist with the Marine Mammal Stranding Network in the San Juan Islands. They often provide first-line veterinary response when pups are picked up and transported to the rehab center.

Wild seal capture:

The wild-weaned seals were captured by the investigation team from a haulout location in the San Juan Islands.

Keep your distance from marine mammals:

We always like to remind people that Federal law requires everyone to stay at least 100 meters away from marine mammals like Harbor Seals. Do not approach pups you think are stranded or abandoned. They may be just waiting for their mother to return, but if you approach you may scare off the mother and cause the pup to be abandoned.

Harbor Seal facts:

Did you know the milk of harbor seals is 40% fat? Or that they can dive up to 600 feet? View more harbor seal facts.

Harbor Seal skeleton available for display:

SeaDoc has a mounted skeleton of a large male harbor seal found dead on a beach in San Juan County. The skeleton travels to schools, banks, and other public display locations to help people learn about Salish Sea marine mammals. If you're interested in displaying the skeleton at your place of business, get in touch. See pictures.

Surprise your friends with a Harbor Seal ringtone:

Just for fun, we took a recording of a squawking young seal and turned it into a ringtone for the iPhone. It sounds a little bit like a badly out-of-sorts child, and definitely gets some strange looks in the grocery store. Details.

Defenders of the Salish Sea

This story first appeared in UC Davis Magazine, Volume 29 · Number 4 · Summer 2012

At a UC Davis outpost in the Pacific Northwest, wildlife veterinarians work to heal an ocean.

EASTSOUND, Wash. — "Watch out for the otter scat," warns UC Davis wildlife veterinarian Joe Gaydos, as he points to several tidy pink-crustacean-tinged piles on a dock. A glance over the edge of the dock reveals a world of anemones and algae swaying in the incoming tide. And overhead, a pair of courting bald eagles circles above the cedars in a gray February sky.

EASTSOUND, Wash. — "Watch out for the otter scat," warns UC Davis wildlife veterinarian Joe Gaydos, as he points to several tidy pink-crustacean-tinged piles on a dock. A glance over the edge of the dock reveals a world of anemones and algae swaying in the incoming tide. And overhead, a pair of courting bald eagles circles above the cedars in a gray February sky.

These stunning views — on shore, under water and in the air — offer glimpses of the expansive "laboratory" of the SeaDoc Society, an outpost of the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center on Orcas Island, the largest of Washington state's San Juan Islands. Through science and education, SeaDoc is working to protect the health of marine wildlife and their ecosystems 700 miles north of Davis in the Salish Sea. One of the world's largest inland seas, it covers more than 10,500 square miles, encompassing Washington's Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the San Juan Islands, as well as British Columbia's Gulf Islands and the Strait of Georgia.

"The Salish Sea is one of the most amazing places on Earth and people who live here want to pass on a healthy ecosystem to future generations," says Gaydos. "SeaDoc's work is to make sure there will still be amazing wildlife, abundant fish and shellfish to eat and clean water for people and for wildlife far into the future."

The waters and shores of the Salish Sea are the shared home of 37 species of mammals, 172 species of birds, 247 species of fish, more than 3,000 species of invertebrates and nearly 6 million people. This lush ecosystem includes killer whales, bald eagles, Pacific salmon, abalone, crabs and clams. Indeed, the species count is one example of SeaDoc's work here — a report that Gaydos co-authored in 2011 included the first compilation of birds and mammals that depend on the Salish Sea.

But a growing number of those species are in decline — another SeaDoc finding. Since 2002, SeaDoc has tracked the overall number of wildlife species that are listed as threatened or endangered in the Salish Sea; from 2008 to 2011, that number nearly doubled, from 64 to 113.

A powerful partnership

How and why the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center established the SeaDoc Society so far from campus is a testament to the center's reputation as well as a local couple's commitment to restoring the health of the Salish Sea.

In the late 1990s, philanthropists Ron and Kathy McDowell of the San Juan Islands began looking for an institutional partner with the right credentials — high-caliber academics and a good history of working on ecosystem-level problems — to study and enhance the health of the Salish Sea. Impressed with the School of Veterinary Medicine's talented faculty and its Wildlife Health Center's applied, problem-solving approach to conservation and health, the McDowells considered the school a perfect partner for developing a new program — one that would apply the veterinarian's patient-oriented skills, not on individual animals, but on the whole ecosystem.

Then-Dean Bennie Osburn reasoned that if the veterinary school could run programs in Africa, it certainly could run one in Washington state. Osburn tapped the Wildlife Health Center for the program. Veterinarian Kirsten Gilardi was named director; Gaydos, a veterinarian specializing in medical microbiology and wildlife diseases then working at the University of Georgia, was brought on as regional director and chief scientist.

Gilardi and Gaydos quickly established what today has evolved into a unique marine ecosystem health program — one that combines new research into critical questions about the management of the Salish Sea, science translation that ensures that the information is getting into the hands of policymakers and the public, and the close involvement of citizens providing input and support. The SeaDoc Society recently celebrated its 10th birthday, and in this short time has become a key player in marine conservation in the Salish Sea.

"To me, the most interesting thing about SeaDoc is the fact that it's a private/public partnership," says Gary Davis, chair of SeaDoc's board of directors and a former senior scientist with the National Park Service. "It's a small group of citizens interested in collectively doing something to improve the environment. It's a powerful combination when supported by an institution like the University of California, particularly the Wildlife Health Center and the School of Veterinary Medicine. It means you can do things in a different way."

With just five employees at the Orcas Island headquarters, and a shoestring annual budget of about $500,000, SeaDoc depends on citizens' involvement, Gilardi says. "SeaDoc is largely funded by private gifts and most of our donors are local, so they feel incredibly connected to — and partly and rightfully responsible for — the success of SeaDoc's work in the Salish Sea," she says. "It's what makes SeaDoc unique: the university working hand-in-hand with concerned citizens to get essential science done that conserves wildlife and helps to heal the ocean."

One Sea, One Health

Even the name of the Salish Sea reflects the work of the SeaDoc Society. Formerly known as Puget Sound and Georgia Basin, the inland sea was renamed by the U.S. and Canada in 2010 in honor of the Coast Salish, the people who have inhabited the region for millennia.

"SeaDoc really pushed for adopting the new name 'Salish Sea' because it drives home the concept that this is a whole ecosystem, regardless of political boundaries," says Gaydos.

Since international borders are invisible to fish and other wildlife, the SeaDoc Society recognized that healing Washington's inland waters was going to require an approach that "treated" the inland waters as a whole entity, rather than as a sum of parts, much as a veterinarian approaches an individual patient.

This holistic view of the marine region, and the people and animals that live in it in a connected interdependence, is in keeping with the Wildlife Health Center's focus on One Health, a philosophy that recognizes that the health of the environment is essential for the health of wildlife, domestic animals and people — and vice versa.

Informing policy

SeaDoc's success in translating science is evident in the growing number of policymakers who seek its help. Groups like the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, the Washington governor's office, Washington State Legislature and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife regularly ask SeaDoc to provide the current state of science on a particular issue so that a sound management or policy decision can be made.

As Gaydos says, "Science is great because it gives us the facts that help us make good decisions and inspire people to want to care — to want to save a place."

For more than eight years, SeaDoc has hosted a winter lecture series. Gaydos, who was hired as a translational scientist, gives an average of two professional presentations a month. He also sits on a number of science panels, including the Puget Sound Partnership Science Panel, which is charged with restoring Puget Sound by 2020. Martha Kongsgaard, chair of the Puget Sound Partnership, says "SeaDoc plays a unique role in not only producing essential science, but, as importantly, in integrating that science into environmental policy."

Gaydos and his collaborators conduct research on how disease impacts wildlife populations. In addition, using privately donated funds, SeaDoc awards competitive grants to scientists to focus on the marine ecosystem or on the threatened and endangered species that live in it. Those species include the following:

River otters Those telltale signs of otters on the dock provide evidence for a scientific study on how the predators, which eat up to 15–20 percent of their body weight in food every day, could affect salmon and rockfish populations.

River otters Those telltale signs of otters on the dock provide evidence for a scientific study on how the predators, which eat up to 15–20 percent of their body weight in food every day, could affect salmon and rockfish populations.

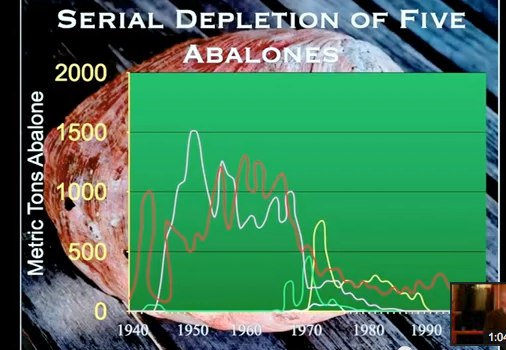

Northern (pinto) abalone A number of funded studies looked at why the population of this native mollusk had not recovered, but rather declined, since Washington and British Columbia banned their recreational harvest in the 1990s. One project examined genetics, another looked at hatchery release techniques, a third studied interactions of pinto abalone with other species, and a fourth explored whether aggregating animals left in the wild helps them breed.

The results: the discovery of a subspecies that improved hatchery breeding, and a finding that hatchery young are less likely to become merely crab bait if placing in the sea is delayed until they grow to about 1 inch in diameter. These and other scientific discoveries formed the foundation for what is now an active statewide recovery program.

Western grebe A bird so aquatic that it can't even walk on land and builds floating nests, the Western grebe has declined by 95 percent over the past several decades in the Salish Sea. Although once there were flocks of 3,000 to 5,000 in Bellingham Bay, Gaydos and his colleagues now get excited when they see 50. Gaydos and collaborators have improved a surgical procedure to allow scientists to implant transmitters in these birds to track their migratory patterns and better understand their decline.

Killer whales Three distinct types of killer whales, or orcas (Orcinus orca), live in the Salish Sea. The most commonly encountered are the fish-eating "resident" orcas. These whales are salmon eaters, preferring Chinook, as shown in recent studies. Less commonly seen are the marine mammal-eating "transient" killer whales. Occasionally, "offshore" killer whales are spotted in the Salish Sea and are thought to be fish and shark-eaters. All three ecotypes of killer whales are state and federally listed as endangered.

Killer whales Three distinct types of killer whales, or orcas (Orcinus orca), live in the Salish Sea. The most commonly encountered are the fish-eating "resident" orcas. These whales are salmon eaters, preferring Chinook, as shown in recent studies. Less commonly seen are the marine mammal-eating "transient" killer whales. Occasionally, "offshore" killer whales are spotted in the Salish Sea and are thought to be fish and shark-eaters. All three ecotypes of killer whales are state and federally listed as endangered.

Killer whales from the Salish Sea are some of the most contaminated marine mammals in the world, and pollutants are considered a factor in causing the decline of the southern resident population. The Salish Sea has very high levels of legacy PCBs, chemicals once widely used in manufacturing electrical equipment and a variety other products. SeaDoc has ensured critical research to look at contaminants in salmon and how they affect the killer whales that eat them. SeaDoc has also conducted research examining the role of disease in the declining killer whale population.

On the other hand, one species that is doing well is the harbor seal, and its story is a testament to what can be done when species-appropriate action is taken. In 1972, following studies that had shown a precipitous decline in the harbor seal population, the U.S. passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which has enabled the Salish Sea's population of harbor seals to bounce back and stabilize, from about 2,000 to around 12,000 animals. The Salish Sea population is now one of the most dense harbor seal populations found anywhere in the world. Stories like this can move the public to advocate for measures that will give other species a chance.

Far-reaching impacts

SeaDoc's ability to assess the ocean's ills, diagnose ecosystem health ailments and propose solutions or cures for them has resonated well beyond the Salish Sea. The group also sponsors research along the California and Baja California coasts and coordinates a West Coast program to clean up derelict fishing gear, which kills marine life.

That's not to say there aren't frustrations for the SeaDoc team. "Sometimes it does get hard. You get frustrated that recovery isn't moving fast enough or worried that we're not raising more money," Gaydos says, "because we know the amount of work that still has to be done.

"But one good part of my job is that I get to see all the good work that is happening — on salmon and killer whale recovery, on restoring estuaries. So, we're making progress, and a lot of people really do recognize the importance of SeaDoc's work. That's hugely gratifying."

New research on causes of stress in Killer Whales

Marine Science: Can it Help the Salish Sea?

Joe Gaydos delivered the keynote talk, "Marine Science: Can it Help the Salish Sea," at the Sound Waters conference in Langley, WA. Organized by Island County Beach Watchers, this conference was a full day of informative classes and sessions.

Video: Thor Hansen on Feathers, November 2011

Hanson's 2011 book, Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle, investigates not only the evolution and mechanics of feathers, but also their cultural importance and their role in technological innovation. It got rave reviews in the national press. Add to that Hanson's engaging and enthusiastic speaking style, and you've got a talk that shouldn't be missed.

John Elliott wins 2011 Salish Sea Science Prize

Scientist Who Helped Eliminate Toxic Chemical Flows Into Salish Sea Honored

October 27, 2011

BC Scientist John Elliott, who helped eliminate dioxin and furan discharge into the Salish Sea, is honored with the SeaDoc Society’s prestigious Salish Sea Science Award.

Dioxins and furans are highly toxic persistent organic pollutants that once were dumped into the Salish Sea in pulp mill effluent. They are counted among the twelve most poisonous “dirty dozen” toxins in the world, and once were concentrated in fish and fish-eating birds in British Columbia, causing fishery closures and waterfowl consumption advisories. Thanks to mandated changes in bleaching processes and restrictions on usage of the parent compounds for these toxic chemicals at pulp mills, discharge of dioxins and furans into the Salish Sea has been eliminated.

Dioxins and furans are highly toxic persistent organic pollutants that once were dumped into the Salish Sea in pulp mill effluent. They are counted among the twelve most poisonous “dirty dozen” toxins in the world, and once were concentrated in fish and fish-eating birds in British Columbia, causing fishery closures and waterfowl consumption advisories. Thanks to mandated changes in bleaching processes and restrictions on usage of the parent compounds for these toxic chemicals at pulp mills, discharge of dioxins and furans into the Salish Sea has been eliminated.

Today a toxicologist from Environment Canada, Dr. John Elliott, was awarded the prestigious Salish Sea Science Prize in recognition of his research documenting the presence and effects of these chemicals on wildlife and his work with regulators to translate his science into policy that eliminated the release of these chemicals into the ocean.

Dr. Elliot began his work in the mid-1980s with research on great blue herons, to better understand the possible effects of persistent organic pollutants on these aquatic birds. As part of a team that included population biologists, chemists and biochemists, Elliot documented for the first time the exposure of wild birds to the forest industry derived pollutants, dioxins and furans. As well, he documented high concentrations of these chemicals in bald eagles living near pulp mill sites, and went on to determine the deleterious effects of these toxins on eagles breeding near contaminated areas. His initial studies led to further research demonstrating the effects of these chemicals on embryonic development of both herons and cormorants at colonies near pulp mills and other forest industry sites in the Salish Sea.

Dr. Elliot began his work in the mid-1980s with research on great blue herons, to better understand the possible effects of persistent organic pollutants on these aquatic birds. As part of a team that included population biologists, chemists and biochemists, Elliot documented for the first time the exposure of wild birds to the forest industry derived pollutants, dioxins and furans. As well, he documented high concentrations of these chemicals in bald eagles living near pulp mill sites, and went on to determine the deleterious effects of these toxins on eagles breeding near contaminated areas. His initial studies led to further research demonstrating the effects of these chemicals on embryonic development of both herons and cormorants at colonies near pulp mills and other forest industry sites in the Salish Sea.

In countless meetings and presentations, Elliot worked with industry and regulators to communicate this science and in so doing, influenced subsequent national and international regulations that halted the use of molecular chlorine bleaching, and restricted the use of chlorophenolic wood preservatives and anti-sap stains. This was no small accomplishment, as during that time, the forest industry was the economic mainstay of many of the communities around the Salish Sea.

For this work, Elliot was selected as the winner of the SeaDoc Society's 2011 Salish Sea Science Prize. This prestigious $2,000 no-strings-attached prize is the only award of its kind. It is bestowed biennially by the SeaDoc Society to recognize a scientist whose work has resulted in the demonstrated improved health of fish and wildlife populations in the Salish Sea. It is given in recognition of, and to honor the spirit of, the late Stephanie Wagner, who loved the region and its wildlife.

While awarding the prize today at the 2011 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference in Vancouver, BC, Dr. Joe Gaydos, Chief Scientist and Regional Scientist for the SeaDoc Society, said that Elliott’s work “served as an example to the world for how science can make a positive difference and is a crucial foundation for designing healthy ecosystems.”

Killer Whale Ringtone

2011 Rockfish Recovery Workshop recap

This past week (June 28 & 29, 2011) SeaDoc co-hosted a Rockfish Recovery Workshop in Seattle with the State Department of Wildlife and NOAA Fisheries.

Nearly 100 scientists, fisheries managers, fishers and SCUBA divers attended the 2-day workshop to discuss the current state of knowledge on rockfish and to identify future needs related to recovering depleted rockfish populations in the Salish Sea.

There are 28 species of rockfish in the Salish Sea. Thirteen (13) are listed as species of concern and recently 3 species were listed under the US Endangered Species Act.

There are 28 species of rockfish in the Salish Sea. Thirteen (13) are listed as species of concern and recently 3 species were listed under the US Endangered Species Act.

In addition to helping organize the workshop, SeaDoc also helped bring in Canadians to share their perspective on what has and has not worked with rockfish recovery on the other side of the border.

A lot of the research SeaDoc funded over the last 10 years was presented and plans were laid for moving rockfish recovery forward. The meeting proceedings will be published soon and will be available here on the SeaDoc website.

In the meantime, here's a recap:

(Please note that this summary is taken from my notes and if there are errors or misstatements they are mine, not the researchers/presenters! -Joe T.)

Historical Context Session

Wayne Palsson spoke on the biology and assessment of rockfishes in Puget Sound. Rockfishes are a diverse group of species with different life histories. They require various habitat during different life stages. They are adapted for slow growth, long survival, late maturity, low natural mortality rates, and high habitat fidelity. These are all factors that make recovery tough. There's a lack of long-term data that makes it hard to create conventional age-structure population models and biomass dynamic models.

Chris Harvey reviewed the ecological history of rockfish exploitation in Puget Sound. Rockfish bones have been found in middens dating back 1,500 years. Much of the fishing pressure on rockfish began after the Boldt decision in 1974, which required that harvests in Puget Sound be coequally managed by the State government and the Treaty Tribes of Washington. It's also been influenced by demographic trends and by the promotion of the fishery by State government. (Unfortunately, as covered in Wayne Palsson's talk, it wasn't until 1982 that scientists learned that rockfish were generally 2 to 3 times longer lived than they'd thought, which meant the existing population models were not accurate.) By the time management efforts were deemed necessary, the greatest harvests had already occurred.

Anne Beaudreau discussed her work to reconstruct historical trends in rockfish abundance. The lack of data on historical populations of rockfish is a major barrier to developing sustainable fisheries. Beaudreau and colleagues interviewed 101 individuals ranging in age from 24 to 90 years to try to derive trends in the abundance of rockfish from 1940 to the present. Of particular interest was the evidence of "shifting baselines." To a statistically significant degree, each age group of respondents interpreted the conditions at the beginning of their awareness as "abundant" and saw declines from there, but what was "declining" to an older person was "abundant" to a younger person.

Benthic Habitat Surveys/Rockfish Abundance Estimates Session

Gary Greene presented the Salish Sea sea floor mapping project, which has produced bathymetric and habitat maps of the San Juan Islands area. Rockfish prefer particular habitat types, and the multibeam echosounders used by Greene and his colleagues allows these potential habitat areas to be identified. (Other participants were very interested in having these maps for other areas in the Salish Sea.

Bob Pacunski spoke on work to use non-lethal methods to survey rockfish populations. Traditional trawl or long-line sampling results in fish mortality, but using a small remotely-operated vehicle has been shown to be effective at providing population surveys.

Stressors Session

Joan Drinkwin of the Northwest Straits Foundation spoke on the threat posed to rockfish by derelict fishing gear, including both nets and traps. The Northwest Straits Initiative has removed 3,860 nets from Puget Sound, all at less than 105 feet deep. There are 950 shallow-water nets still in the water, and at least 70 in deeper water. Based on studies of net mortality by the SeaDoc Society, approximately 1,600 rockfish per year are captured and killed in derelict nets each year in the United States portion of the Salish Sea.

...More coming soon...

Pacific White-Sided Dolphin Population Study

Bears and Barnacles: The Land - Sea Connection

Videos

Why make a list of all the birds and mammals that depend on the Salish Sea? Joe Gaydos explains. (1:18)

Part 2: Why has this never been done before?

In Part 3, Joe talks about:

- the challenges in assembling the list,

- how it can help scientists (including SeaDoc's own Dr. Nacho Vilchis),

- how the list indicates when and how heavily different species use the ecosystem,

- how they tracked down citations for each and every species, and how fox and beaver have been shown to use the intertidal zones.

At about minute 4:30 Joe talks about how the tidal marsh beavers not only use the marine resources, but also contribute to the health of salmon populations. Pretty interesting stuff.

Click to see a picture of a beaver dam in the Skagit River delta.

Get the Checklist

We've created a printable checklist of all the bird and mammal species that depend on the Salish Sea.

We've created a printable checklist of all the bird and mammal species that depend on the Salish Sea.

You can print the checklist on two sides of a single sheet of paper and take it with you on your travels.

Read the scientific paper

Click here to go to the citation page where you can find a link to the scientific paper.

The Photographer

Big thanks to Jim Braswell for sharing his extraordinary images. Please visit Jim's nature photography site at http://www.showmenaturephotography.com where you can see more of his photographs and learn about his photography & photo editing workshops.

Share This Page

Click below to share this page by email or on your favorite social media site.