Peer-reviewed publication:

Vilchis, L. I. C. K. Johnson, J. R. Evenson, S. F. Pearson, K. L. Barry, P. Davidson, M. G. Raphael, and J. K. Gaydos. 2014. Assessing Ecological Correlates of Marine Bird Declines to Inform Marine Conservation. Conservation Biology. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12378. (Open access publication)

Where have all the birds gone?

The last 30 years have seen precipitous declines in many of the bird species that visit the Salish Sea during the winter.

Using various tools, private money and strategic collaborations, SeaDoc made a substantial investment to understand the problem of declining marine birds. We recently completed research demonstrating that diving birds that eat schooling forage fish are the species most likely to be in decline.

Tackling such a big issue is not easy. Understanding how we worked through this issue gives you a good idea of how SeaDoc can address what might seem to be insurmountable obstacles to healing the Salish Sea. It also shows you how private support makes our work possible.

Step 1: Identify the information gap

In 2005, SeaDoc brought researchers and managers from the US and Canada together to talk about the state of marine bird populations in the Salish Sea. It became clear that we were facing a big problem. Birds were declining in different jurisdictions, but it wasn’t clear how steep the declines were, which species were involved or what factors were behind these declines.

Because no one took a big-picture approach, bird restoration efforts were focused on one species at a time. But was there something going on at the ecosystem level causing multiple species to be declining?

We realized we needed an ecosystem-level look at which species were in decline and why.

Step 2. Get around transboundary roadblocks

Decades worth of data had been collected in Washington and British Columbia by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), Audubon, and Bird Studies Canada. But the organizations used different survey techniques and geographic scales so people had not been able to look at the data to get a perspective for the entire ecosystem.

SeaDoc was the ideal group to take on the challenge of merging these differing data sets from two different countries. State, provincial, and federal governments rarely have the time for this kind of effort. Also they have political constraints and pressures that make it hard to see past their borders.

Step 3. Hire a scientist to do the work

Collaborating with multiple groups, merging complex data sets and analyzing decades of data is a full time job for several years. Stephanie Wagner, a woman who loved the Salish Sea and its creatures, made a legacy gift to SeaDoc before she died. This gift provided the funding that allowed us to hire Dr. Nacho Vilchis to lead this important work.

Step 4. Use an epidemiological approach

Dr. Vilchis' first task was to get the data sets to “talk to each other.” WDFW conducts aerial transects from a plane. Bird Studies Canada and Audubon use point counts. Both are good techniques, but they produce surveys that are difficult to compare.

Nacho, who has a background in the statistical manipulations of large data sets, found a way to combine and use the three surveys in one overall analysis. Then he trimmed the set down to just 39 core species, removing the occasional visitors and the birds for which he didn’t have enough data to draw robust conclusions.

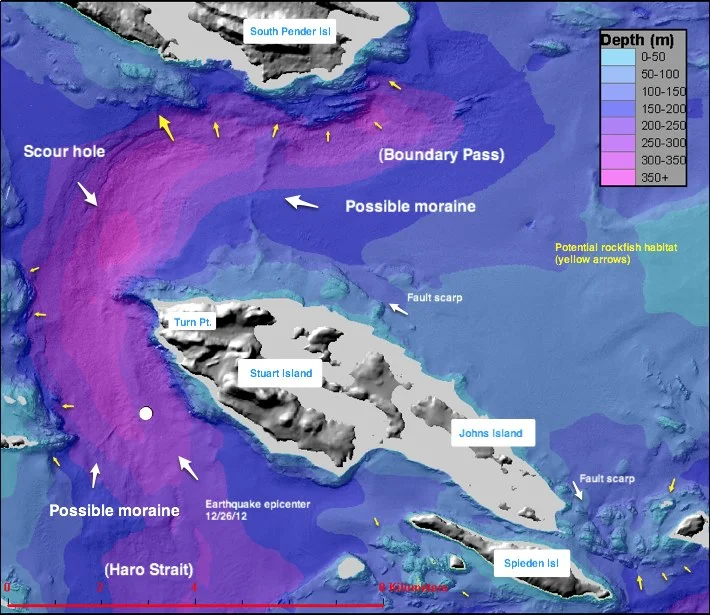

He also used GIS maps of the Salish Sea to connect each data point not only to a geographical area but also to major habitat characteristics, such as water depth.

Drawing heavily on the “Doc” part of SeaDoc, we used an epidemiological approach to find a likely diagnosis. Just as the family doc quizzes you for risk factors for diabetes or heart disease, SeaDoc found that two lifestyle factors among seabirds correlated to a very high risk of population decline.

Step 5. Translate results into recovery

The work, published in the internationally-acclaimed peer-reviewed journal Conservation Biology, showed that birds that dive to find food are much more likely (11 times as likely) to be in decline compared to non-divers.

But it’s worse if you’re a diver on a restricted fish diet. Diving birds that focus their efforts on small schooling fishes called forage fish were 16 times as likely to be in decline. Forage fish are small schooling fish that convert plankton into fat and are eaten by other fish, birds and mammals. These include herring, smelt, anchovies, eulachon, sardines, and sand lance.

But publishing a paper is not the end. It actually is just the beginning. This paper is now being used by scientists, managers and policy makers as evidence for the need to recover marine birds. Recovering forage fish will not just benefit birds, however. Because forage fish turn plankton into fat that’s available for other animals, they are a key part of the ecosystem and their recovery will benefit salmon, lingcod, rockfish, harbor porpoise and many other species within the Salish Sea.

Four key factors made this project successful.

1. Good data

Dr. Vilchis could not have conducted this analysis without scientists and citizens having already spent decades collecting rigorous data. The collection of these data took money, persistence, and forethought.

2. Collaboration

From the beginning, this project has been a story of collaboration. From the individuals collecting data over two decades to the senior scientists who worked out a way to share their data, it’s taken the work of many people working in different jurisdictions to make this happen. Our collaborators shared three huge datasets collected on two sides of an international border. They only did so because they were confident that SeaDoc would be able to use the data to produce robust scientific results.

3. Working on the level of the ecosystem, not the politics

This was the first study to look at bird declines across the entire Salish Sea marine ecosystem.

Most Canadian or US maps stop at the border, but the Salish Sea does not. Too often, the mandates and responsibilities of the people who work at the various state, provincial, and federal agencies tasked with keeping wildlife populations healthy also stop at the border.

SeaDoc, being privately supported by people like you who understand how important it is to treat the ecosystem as a whole, works across the entire ecosystem.

4. An extraordinary legacy gift

In the end, one person's financial gift made this project possible.

Without Stephanie Wagner’s legacy gift, this project would have been just a good idea that never got done. Instead, we made it someone’s job to find the truth that was hidden in the data.

Stephanie Wagner’s thoughtful gift enabled us to point clearly to a hidden problem affecting the productivity of the entire Salish Sea ecosystem. With her gift we were able to do good science that will make a difference in how scientists and managers work on healing the Salish Sea.

Put plainly, money can change the world for the better.

Please contact SeaDoc or your financial advisor if you’re interested in including SeaDoc in your will so you can leave a legacy for the health of the Salish Sea.

At the 2014 North American Veterinary Conference, in Orlando, Florida, Joe Gaydos presented on Salmonella in wildlife. About 10% of the Salmonella outbreaks between 2006 and 2013 were caused by wild animals, and most of these were caused by reptiles and amphibians.

At the 2014 North American Veterinary Conference, in Orlando, Florida, Joe Gaydos presented on Salmonella in wildlife. About 10% of the Salmonella outbreaks between 2006 and 2013 were caused by wild animals, and most of these were caused by reptiles and amphibians.

At the 2014 North American Veterinary Conference, held in Orlando, Florida, Joe Gaydos presented a paper on diseases in river otters.

At the 2014 North American Veterinary Conference, held in Orlando, Florida, Joe Gaydos presented a paper on diseases in river otters.

October 2013: NOAA Fisheries is removing the eastern Distinct Population Segment of Steller sea lions from the list of threatened species, because it has met its recovery criteria as outlined in the 2008 Steller Sea Lion Recovery Plan and no longer meets the definition of a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This makes the eastern population of Steller sea lions the first species NOAA has delisted due to recovery since 1994, when the eastern North Pacific gray whale was taken off the list of threatened and endangered species.

Read more:

October 2013: NOAA Fisheries is removing the eastern Distinct Population Segment of Steller sea lions from the list of threatened species, because it has met its recovery criteria as outlined in the 2008 Steller Sea Lion Recovery Plan and no longer meets the definition of a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This makes the eastern population of Steller sea lions the first species NOAA has delisted due to recovery since 1994, when the eastern North Pacific gray whale was taken off the list of threatened and endangered species.

Read more:

We've created a printable checklist of all the bird and mammal species that depend on the Salish Sea.

We've created a printable checklist of all the bird and mammal species that depend on the Salish Sea.