Many of us made New Year's resolutions to lose weight. And those of us of a certain age bemoan the fact that humans hit our biological primes well before middle age.

But did you know that it's much different for fish? Take, for example, our own rockfish. Nearly 30 species of rockfish live in the Salish Sea, and some of them don't become sexually mature until they're 20 years old – that's two decades of avoiding hungry mouths, baited hooks and nets until they can even begin to breed. Once they do, though, the female rockfish gives birth to live young and we believe she continues to reproduce her entire life span, which for some species can be more than 100 years!

And when it comes to fish, fat mommas are the best as the older and bigger the female gets, the more babies she'll have each year. A study of one rockfish species showed that while small females produced around 5,000 embryos, larger ones could carry a whopping 700,000.

Most of our rockfish species are in serious decline. Knowing what we do of their slow-growing, late-blooming and long-breeding life cycle, it's obvious that protecting the big beautiful mothers is the key to recovery. That's where Marine Reserves can help. These nursery areas protect the large females so they can reproduce and create young that disperse and populate areas where fishing is allowed. Or at least that's the general theory…

But it takes a lot of great science before we can intelligently decide the best way to keep our seas healthy. SeaDoc funded a study by Dr. Lorenz Hauser and colleagues from the University of Washington and the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife to learn how effective reserves were for Brown Rockfish.

But it takes a lot of great science before we can intelligently decide the best way to keep our seas healthy. SeaDoc funded a study by Dr. Lorenz Hauser and colleagues from the University of Washington and the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife to learn how effective reserves were for Brown Rockfish.

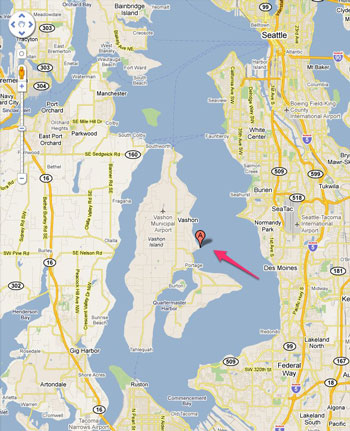

Divers went to Point Heyer (see map), an isolated artificial reef off of Vashon Island, and captured fish just long enough to clip fins so the team could identify genetic markers called microsatellites. From these, Dr. Hauser's team found that only 10% of the young born at the sample site stayed on the home reef.

It's good news that most of the young are dispersing and populating other areas. But with most of the fish moving out of the reserve, are enough staying behind and being allowed to mature in protected areas to replace the big mothers when they die?

Dr. Lorenz Hauser comments, "We wanted to see whether fish reproduce locally or disperse all over the Sound. In the first instance, a single MPA of sufficient size could sustain a population, while in the latter case a network would be required. We showed that most of the fish settling at Pt Heyer were born elsewhere, supporting the latter scenario."

This project is a great example of how SeaDoc targets our research funding to bring maximum return.

SeaDoc was an early investor in Dr. Hauser's research. Our initial funding enabled him to collect preliminary data in order to secure a grant from Washington Sea Grant. Every dollar spent by SeaDoc resulted in about 12 dollars of total research spending that wouldn't have happened otherwise.

Here's a direct link to the original publication that resulted from this research. You can also visit the project website at http://faculty.washington.edu/lhauser/Nemo.html. This site gives a general overview of how the genetic studies work and of otolith microchemistry. (It's worth following the link to the Alaska Fisheries Science Center where you can try counting otolith bands for yourself.)

Want to know even more about this study? Here's an excellent article by Alex B. Berezow, Ph.D. on the Washington Sea Grant website.

Science enables us to invest wisely in designing marine reserves and a healthy Salish Sea. Your donations are helping us answer the important questions. Thank you.