Locals throughout the Salish Sea have long told stories of coastal cutthroat trout, with their distinctive blood-red slashes at the base of their jaws, flourishing right here in our streams. That’s far from the case now, but it was enough evidence for SeaDoc to fund a unique collaboration of scientists to scout the small streams of the San Juan Islands for these native “cutts,” the least-studied of all local salmonid species.

That team of scientists from Wild Fish Conservancy, Long Live the Kings, Speckled Trout Consulting, Kwiaht, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife recently published their findings in Conservation Genetics. You can read it in full here: Genetic composition and conservation status of coastal cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki) in the San Juan Islands, Washington. The paper was written by Jamie Glasgow, Jennifer D. De Groot, and Maureen P. Small.

As we shared shortly after the study was conducted, SeaDoc sent the team of scientists, armed with underwater cameras and “electrofishers,” to several creeks on Orcas and San Juan Islands.

Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki) are the least studied of all the salmonid species, overshadowed by the much larger and higher-profile Pacific salmon: Chinook, sockeye, coho, chum and pink. Similar to their better-known cousins, they are anadromous, meaning they can move between saltwater and fresh to reproduce, although some spend their entire lives in fresh water.

Also like other Salish Sea salmon, coastal cutthroats are under intense pressure throughout their range from habitat impairment including those from development, forestry, pollution from agriculture and stormwater runoff, and fish passage barriers at road crossings, of which the state estimates there are approximately 40,000. The creation of artificial ponds is a particular problem on the islands, as it restricts the movement of trout throughout the watershed, increases water temperatures and decreases oxygen levels within already low-flowing streams, and in one recent case, contributed to the loss of a population of coastal cutthroat trout on Orcas Island. Like salmon, coastal cutthroat trout populations can also be impacted by recreational fishery and hatchery management decisions stocking practices. Introduced fish prey upon native fish, compete for available resources and may interbreed with coastal cutthroat trout, reducing their overall fitness in island streams.

While the San Juan Islands are renowned for being one of the Salish Sea’s most pristine areas, even they are not immune to human impact. And coastal cutthroats are especially vulnerable in places like the islands where streams are small and freshwater habitat is limited. So, as our scientists set out upstream, they couldn’t be sure what they’d find.

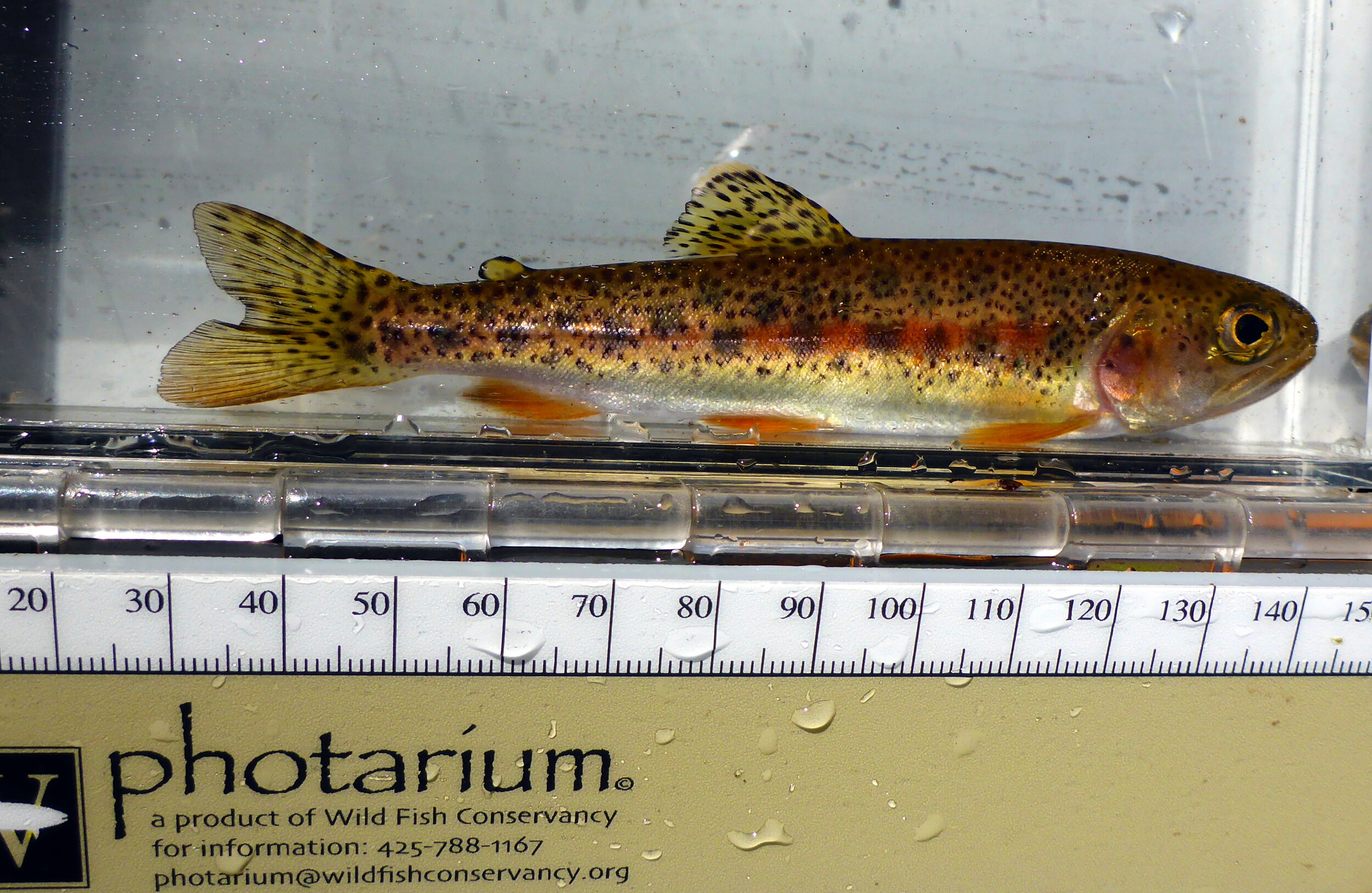

The study revealed that at least three streams on Orcas and the San Juan Islands do indeed have successfully breeding populations of coastal cutthroat trout, each uniquely adapted to their watersheds. Our team used underwater footage and collected DNA from fish before they were photographed, measured, and gently released, unharmed back into their streams.

As we reported at the time of the study:

Two of the streams studied are home to fish endemic to the islands, including one fascinating cutthroat community in Orcas Island’s Doe Bay Creek that has the lowest genetic diversity of any cutthroat population ever tested in Washington State. These beautifully speckled little fish may have been isolated and sustaining themselves in this very limited and unpredictable environment for more than 4,000 years. Talk about hardy!

While it’s great news that the team found these fish, especially the natives, there were not many of them. Each cutthroat stock we found consisted of only about 25 breeding fish, give or take. Already constrained to small patches of suitable habitat, these scant populations are vulnerable to any number of random events including overfishing that could potentially wipe out the entire stock. This vulnerability is compounded by impacts from climate change, which will likely further reduce the amount of wetted fish habitat available during the summertime.

The flip side is that coastal cutthroat trout are survivors. Given healthy watersheds and appropriate protection from recreational fishing and hatchery impacts, they are extremely resilient. Their local adaptations to conditions in their watersheds have allowed them to persist in the Islands’ extremely confined environments. The opportunities to protect and restore their habitats are relatively clear-cut.